When we left off in yesterday’s article, the students of Eastman’s “Realities of Orchestral Life” were just beginning a simulated orchestra contract negotiation. The students of the class represent the musicians in the orchestra and five of their members were designated to serve as their negotiation committee. I represented management and the course professor, Ray Ricker, would act as a mediator if such a need should arise.

The students had just been informed that the financial situation for their “Sim Orchestra” has gone from bad to worse and serious reductions in their annual budget would be necessary to avoid bankruptcy. And so the class continue…

Let The Games Begin

Armed with these new facts the vast majority of the students voluntarily used their entire break to discuss these dire changes and put together a new plan of action. Professor Ricker and I left the room so they could discuss things openly among themselves.

As the second half of the class began, we started the actual negotiation process. The five members of the negotiation committee were lined up across from the management “team” (represented by me) and Professor Ricker stood ready to serve as a kind of ad hoc mediator.

We started things off by my asking the negotiation chair which of the three proposals (detailed in Part 1) they would like to implement. Fortunately, the negotiation committee had other ideas.

Since the members of the negotiation committee were learning via the “sink or swim” method, the process would slip in and out of “simulation” mode so we could establish a rhythm and clarify some ground rules. Such as:

- The members of the negotiation committee didn’t have to obtain my permission to speak by raising their hands.

- Non members of the negotiation committee cold not ask questions or interject during negotiations. Even though they were allowed to view the process, they had to realize that the details of the meeting were being conducted behind closed doors.

- You don’t have to accept an answer at face value.

Once those issues sank in the negotiation committee really started to snap into action.

One of the first things they started attacking was what sort of reductions to the operational expenses were being made at which point I informed them that that the staff has been reduced by 25%; all of which were entry level and part time positions.

The negotiation committee also wanted to know how much the department heads were earning and if they’ve taken a pay cut. I refused to release those figures based on reasons of confidentiality and the result was a good bit of “dialog” exchanged between the two sides, but management finally prevailed (for the moment).

At that point one of the non negotiation committee musicians interjected with a question to management about some of the data that was provided. I had to remind her that non negotiation committee members could not contribute to the negotiation process and that she would have to keep her question to herself until the negotiation committee members meet with the rank and file members.

An aside: That was met with some glowering and visible frustration on her part, but that was a good experience to prepare her for real life. Often, non committee members are kept in the dark about the proceedings. They may know there is something bad happening but they can’t obtain details. It’s a helpless and disturbing feeling.

The student in question dealt with her frustration by leaning over to one of the committee members so she could whisper her question into their ear; not unlike the sort of conversations that go on around the inside of a bar or over the phone.

The next issue (which I felt comfortable in assuming was instigated by a non negotiation committee musician) surrounded the legitimacy of the financial information that management provided; they wanted to know if the figures were accurate. Management told them the board assures everyone that the audit procedures were meticulous and the information provided them was correct.

An aside: The look on the face of one of the negotiation members at that moment was priceless. He was doing an admirable job of choking down the urge to scream “LIAR!”

At that point the students turned to Professor Ricker and asked how much he would “charge” to provide his services to verify the financial information. He was happy to tell them that he would “work cheap”.

So at that point we took a three minute break where the negotiation committee could finally have some open conversation with their musician colleagues and discuss what they wanted to know with newly appointed “Inspector” Ricker and I went out to the hall. Shortly thereafter, Professor Ricker came out to:

- Verify the financial information where we agreed that the financial situation was bad and the numbers were accurate. The significant financial shortfall was due in large part to a locally based large business suddenly and unexpectedly going out of business (GlobalWidgetTech.Com).

- Obtain the salary and qualifications of the Marketing Director (the negotiation committee wanted to know if the director had an MBA) which I told him that because the orchestra can’t afford to pay a Marketing Directing what their for-profit counterpart would earn, we weren’t able to retain as qualified of an individual, but we’re working hard and doing the best we can.

Running to the Edge of the Cliff

Professor Ricker relayed the information to the musicians and they discussed their options for a few more moments, I then returned and the negotiations reconvened. I informed the students that this portion of the negations would represent the final meeting before the expiration of the contract so this was it; we were running to the edge of the cliff.

The negotiation committee immediately informed management that they would not consider either Proposal #2 or #3 and wanted to put forward changes to Proposal #1.

But first, they expressed their concern with the assumption made by management with their projects of reaching an earned income percentage of 45% for the next three years when in the case of the previous year the projected earned income of 45% fell significantly short (29%). They also pointed out that this was one of the reasons the orchestra was obviously in trouble.

An aside: One member of the negotiation committee, Antonio Haynes, was skillfully using his cell phone as a calculator to work through numbers I was throwing their way to very good effect.

Management responded by telling them that with the season being reduced by seven weeks and the fact that we were planning to use some new venues that would charge minimal rent, such as churches, instead of our regular performance hall we would be able to convert the earned income figure of 29% into 45% without having to actually bring in many more new patrons.

Management further explained that it was doubtful that they would be able to really increase their numbers of ticket buyers by any appreciable percentage due to a general decline in interest of classical music that was beyond management’s control.

An aside: I was disappointed that none of the negotiation committee members responded to the fact that 1) the orchestra was abandoning their halls in favor of churches that undoubtedly have inferior acoustics and service facilities and that 2) management really didn’t plan to do anything about bringing in more patrons so much as “adjusting” the concert series to the number of people they were currently bringing in.

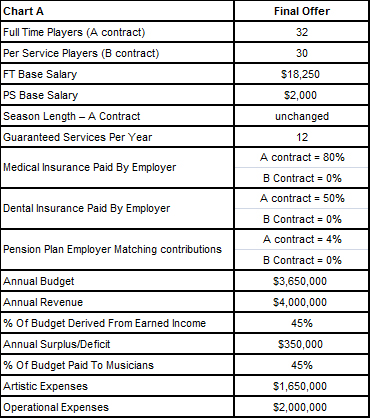

The negotiation committee then launched a new offensive with the goal of determining why operational expenses have been growing so high over the past several years and are still higher than the artistic expenses in all three of management’s original proposals, as portrayed in the following chart:

An aside: I can thank Professor Ricker for pointing that intentionally designed fact out to them.

Management informed the negotiation committee that in order to support a larger orchestra every year they have found it necessary to increase operational expenses in order to attract qualified executive managers and offer year round compensation packages for all staffers.

The orchestra also had to hire several additional part time employees to cover the rise in production expenses due to the expanded seasons. Then there was the significant rise in the cost of professional development for the management staff as well as a sizeable increase in expenditures for consultants to provide crucial support for our augmented development and marketing efforts.

At this point time was quickly running out so a final offer started to take shape. The negotiation committee informed the management that they remaining “A contract” players were willing to accept a reduced season length only if two of those weeks were around the beginning of January and classified as lay-off weeks so they could draw unemployment. In turn, management had to agree to use those funds to establish a guaranteed salary, minimum number of players, and service count for the “B contract” musicians.

This offer brought the annual salary for “A contract” players down about $2,000 and management said it could use those funds to create 30 guaranteed “B contract” positions with a minimum service guarantee that would generate $2,000 in annual income.

Final Offer

Management then presented its “final offer” which the negotiation committee reluctantly accepted to take to the musicians for a vote. The negotiation committee decided to present the offer to the orchestra because management pushed that this was the only way the orchestra would avoid bankruptcy. Management went on to say that the orchestra’s lending institutions would only extend their line of credit so they could continue to carry their current debt IF the musicians accepted on of the three proposals.

The Final Vote

When presented with three options: accept management’s final offer, authorize a strike, or extend the contract for a month while continuing negotiations, here’s how the musicians voted:

Of those that eventually voted for “talk & play” it was split about 50/50 between those that would have accepted the contract and those that would have authorized a strike. Unfortunately, we ran out of time before I could determine the ratio between how the “A contract” and “B contract” players voted.

However, the negotiation committee was able to quickly ascertain which issues the players were most unhappy with and wanted them to address during the extended negotiations.

As a result, Sim Orchestra agreed to play & talk for another month in order to resolve the following issues:

- Increasing “B contract” annual compensation

- Curb the alarming increase in operational expenditures compared to artistic expenses.

- Release details for the plan management has achieve the 45% earned income goals.

- Find a way to cover a percentage of health insurance for “B contract” players.

- Using members of the orchestra to replace soloists if they are willing to work for 75% less than typical soloist fees.

Chart B details which portions of the contract have yet to be worked out during the next round of extended negotiations:

I was very pleased to see how quickly the students were able to realize the severity of their situation and develop a collective negotiation strategy. All of the members appears to work very well together, sometimes conferring in small groups and sometime as a whole.

The chairman seemed to take the lead on most discussions but never attempted to enforce his views on other members or prevented any of them from speaking freely. The entire committee appeared to include as many of their fellow musicians as possible during the their two “private” group discussions (or at least that’s what I thought based on what I could see by spying through the tiny window in the classroom door).

Among their accomplishments, I was pleased to observe:

- They were steadfast in their insistence that there be as many guaranteed positions as possible. The “A contract” players were very willing to accept a smaller annual salary in order to create a guaranteed “B player” contract – they weren’t going to sell out their colleagues.

- They wanted to know what management was doing to improve their situation.

- They insisted on verifying the financial information management was providing them and from that point on they took nothing management told them for granted (remember the calculator wielding tuba player on the negotiation committee?).

- They were resolute on issues of the orchestra providing health insurance.

- They were willing to be flexible about issues related to hiring internal members as soloists and some of the associated work rules to that issue.

- They interpreted a reducing in the size and scope of the orchestra as a reduction in their ability to maintain artistic accomplishments.

What I would have liked to see them accomplish:

- They allowed management to bog them down with the “here and now” issues related to the 800 lb gorilla of a deficit. This prevented them from thinking about negotiating issues that would insure the organization didn’t limit its future under the bogus “structural deficit” mentality. Even though I spent time during the initial lecture portion of the class describing this syndrome and its historical roots, they were still blinded by the deficit fire in front of their eyes.

- They didn’t negotiate future increases in return for current concessions, and as a result, they agreed to a one year “renewable” contract that would make establishing future increases extremely difficult.

- They didn’t attack management’s decision to scale down the seating capacity of their venues due to their inability to prevent the steady decline in attendance numbers. Although they did a good job a making the connection between the size of the ensemble and artistic accomplishment, they didn’t make the same connection to their venues and audience attendance.

- They kept working within the constraints of the budget management proposed to them. They were clever at finding ways to work with those numbers to improve the overall situation among players but they never pushed to simply demand that the board and management do a better job at raising more money.

After the class the negotiation chairman, Sebastian Kroll, said that he could see this mock negotiation becoming a course for an entire semester. And I would have to agree, there’s so much the students were learning as the negotiations progressed I can only imagine what they could learn and how well equipped they would be for their future as professional orchestra musicians if one class turned into an entire course.

This class allowed them to think about their profession in an entirely new light from both sides of the negotiation table. The realities of earning a living and having a direct hand in shaping their workplace will soon move from being a mock exercise to a very real part of their lives.

I could see the look of anger, frustration, and disparagement in the student’s faces that were designated as members of the “B contract” as the negotiations progress. They quickly realized that their life of just barley making enough to get by was going to be completely gone. What would they do, how would they make money?

After they get over feeling a little depressed, I hope they see that this class encouraged them to develop a viewpoint regarding these very real issues.

I also hope that the professional musicians out there dealing with many of these same issues can learn something from these students. Many of their behaviors parallel what is happening right now in dozens of orchestra negotiations across the country.

In the end, although this exercise was purely academic and didn’t include the multitude of political posturing normally associated with negotiations, it still served to plant new seeds of thought in the minds of the musicians of tomorrow.

Postscript: I would like to thank Professor Ray Ricker for inviting me be a guest speaker and allowing me complete freedom to design and conduct the mock negotiation. I’m very happy to see a conservatory like Eastman provide their students not only with the artistic training they need to become some of the best musicians in the world, but to also provide the tools they need to ensure that they will be happy with their choice in careers and to become hands-on participants in their industry.