In anticipation of June’s annual Orchestra Compensation Report update, it is always fun to take a look at some of the issues that don’t usually make it into those reports. One item of particular interest is related to the practice of projected base musician salary levels. For those unfamiliar, orchestras negotiate collective bargaining agreements (CBA) with their musicians that determine base wages up to five years in advance. As a result, this allows analyst geeks (like me) to have some prognostic fun…

For decades, the title of “The Big Five” referred to the top five highest budget orchestras which traditionally included Boston Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, and Philadelphia Orchestra. Unsurprisingly, those same ensembles paid the highest base musician salaries. But over the past decade, this group has grown to include the Los Angeles Philharmonic and San Francisco Symphony which has led some to start using the term “Big Seven.”

The latest orchestra in this group to sign a CBA that pushes the maximum date is the San Francisco Symphony, which recently ratified an agreement that lasts through the 2011/12 season. Throughout the term of this contract, their musicians are expected to receive an average 4.33 percent annual increase in base salary (not bad in a time when many in this business have adopted a Chicken Little attitude). At the end of that contract, the San Francisco Symphony projects a minimum base musician salary of $141,700, which is right in line with their traditional salary rate of increase dating back to the 2005/06 season.

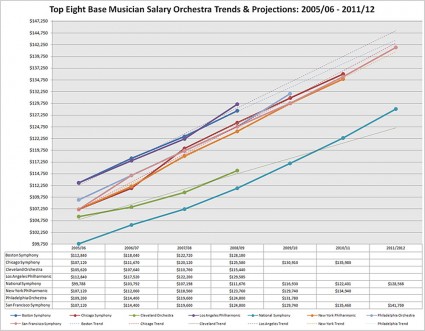

Interestingly enough, when you compare the San Francisco Symphony increase with the increases in base musician salary levels among the remaining Big Seven ensembles, you start to see some interesting developments. For example, using the 2005/06 season as a starting point, most of the Big Seven offered comparable base compensation levels but starting in the 2006/07 season, The Cleveland Orchestra started to fall behind. In fact, while Cleveland’s rate of increase slowed, the remaining six orchestras ramped up a bit or stayed consistent with traditional rates of increase.

This resulted in a compensation gap between Cleveland and the remaining Big Seven orchestras; moreover, this gap becomes even more apparent when you add an eighth orchestra into the mix, the National Symphony Orchestra. Prior to the 2005/06 season, National was closer in base pay levels to the orchestras in Detroit and Pittsburgh than Cleveland. But between 2006/07 and 2008/09, that began to change and at the end of that period, Cleveland and National were only $3,764 apart in base musician compensation whereas Cleveland was a full $8,320 lower than the nearest Big Seven member (New York).

The chart below illustrates trends in base musician compensation for the Big Seven plus National Symphony Orchestra, which is the only other orchestra in this group besides San Francisco that has a CBA in place projecting compensation levels as far out as the 2011/12 season. When a simple, linear trend line is applied to the orchestras that do not have salary levels projected that far, it is clear that Cleveland’s salary gap will not only expand, but their base musician salary level will fall below National Symphony by the 2010/11 season.

Interestingly enough, the remaining Big Seven orchestras continue to maintain projected differences in compensation levels within historic tolerances (although you’ll need to view the full size chart to clearly see those differences). It will be fascinating to see if actual CBA negotiations over the next 16 months produce base salary levels on par with these linear projections and if so, the business might start substituting the term Big Seven for Big Six (unless National decides to leap frog ahead after 2011/12).

It would be interesting to compare this chart with a chart about revenue. Because, let’s take San Francisco, for example. In seven seasons, the base pay increases nearly 35K. Multiply that by 100 musicians or so and you have a expense increase of 3.5M per season after the seventh season. I wonder if ticket sales or other revenue can, or traditionally have, made up for this expense increase.

That’s certainly a well worn topic of discussion but it usually boils down to this: are improvements to employee compensation (musician and management) exceeding rates of inflation and costs of living to obscene degrees? Likewise, are those increases deserved?

Ultimately, the SFS board had to determine that any increases in expenses is something they can support or they wouldn’t have agreed to the contract (at least, that’s the theory but that’s not always the practice – but that’s a different conversation).

I’ve always thought it would be interesting to compare these base salaries to cost of living in each city. My hunch would be that Cleveland would then move to the top of the heap because it’s such a cheaper place to live then Boston or LA or San Fran.

That’s another well-worn discussion but for orchestras in this budget level, being responsible for $250,000+ in instrument expenses makes a large portion of that conversation moot.

An Open Question:

While it may expose my bias, what is the case-rationale for ANY compensation increase in CBA’s in light of current economic conditions? Excepting most of the Big Five, how do union delegates handle and respond to demising resources faced, especially, in the Midwest industrial cities: Cleveland, Detroit, Indianapolis and the like?

My experiences are unions often believe it is the failure of management to increase earned and contributed revenues irrespective of extraneous market forces. Is that generally the sentiment or are there other dimensions?

I know I am probably not the first to observe this, but isn’t there something this industry should be observing with vehement attention to Detroit Big Three (Autos) and the UAW CBA’s?

What’s important to rememebr here is that the economic downturn is impacting orchestras in very different ways. Fro example, I have clients that are actively engaged in growth cycles and although the economy has forced them to make some changes, it hasn’t derailed their growth.

Next, I’m not certain who you are referring to with the phrase “union delegates” as orchestra musicians negotiate their respective master agreements directly. They can, and often do, receive support from local union offices or the Symphonic Services Division of the American Federation of Musicians. In other cases, they hire completely independent negotiators, legal counsel, and/or financial experts to assist in negotiations.

Finally, comparing the financial and labor models of the auto industry to the orchestra business is about as productive as basing artistic programming strictly on the pop music business: Hannah Montana has as much to do with orchestras as the UAW.