Sunday’s Charleston Post and Courier quotes a former board member of the Charleston Symphony as saying “The current business model has proven over 10 years not to be viable.” The recent travails and controversy at the Pasadena Symphony provoked a considerable amount of national discussion, including Terry Teachout asking, in The Wall Street Journal, “What, if anything, justifies the existence of a regional symphony orchestra in the 21st century?”

In recent well publicized cases, musicians have been asked to take staggeringly large pay reductions because boards have concluded that the communities they serve are unwilling to contribute the funds necessary to support the orchestra as it has previously existed, and that only a much smaller orchestra can survive. Do these cases show that the model is dead? Or only that it doesn’t work when it’s not well executed? Or maybe a little bit of both?

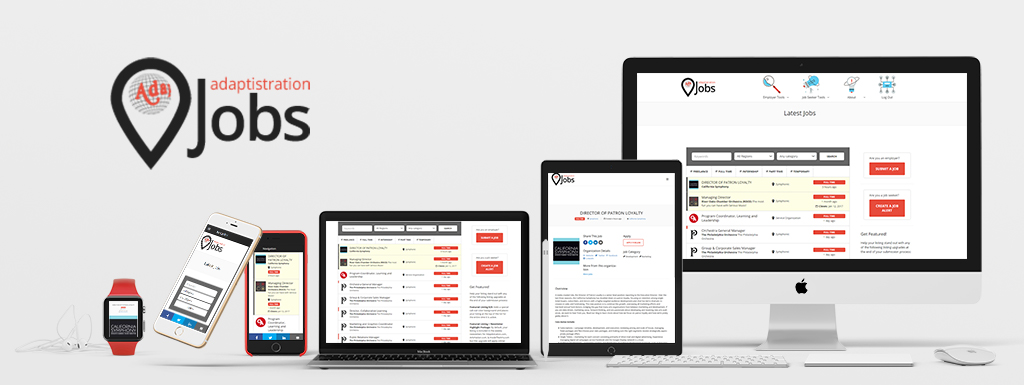

After spending a couple of days looking at what the model is, and why it may no longer apply, I thought I would wrap up my three day guest blogger stint here at Adaptistration by sharing a few ideas on what an updated model might and might not include.

Audiences

I would argue that changes in how many members of our audience participate have significant implications for what any orchestra model has to say about both marketing and programming. And that, on the marketing side, the impact of changes in audience behavior is magnified by the incredible changes we’re seeing in media markets. Many of the tried and true ways of reaching our audience are much less effective than they used to be. Yet we cannot afford to abandon the old ways, while we at the same time strive to very quickly become savvy in using new ways.

If full season subscriptions are no longer the dominant form or orchestra audience participation…does that mean we should forget about subscriptions? Absolutely not! Orchestras still need to run flawless subscription campaigns–marketing departments which pay more attention to updating their Facebook page than the nuts and bolts of the renewal campaign are heading for disaster. But if we live in a world where there are lots of people who will buy tickets for concerts, but are unlikely to ever sign up for a traditional subscription package, doesn’t it go without saying that we also need to apply enormous creativity and resources to selling single tickets? There are plenty or smart people in the field who have been doing this for years, but many of us still seem to see single ticket buyers as a short lived evolutionary stage that people go through on their way to becoming subscribers and eventually major donors at which point they really start to matter. I would argue that ideally every concert should have its own well-conceived and well-executed marketing plan.

On the programming side, I know there are really smart people out there who disagree with me, but I often argue that in the traditional orchestra model you maximized ticket revenues by playing to the base, but in the new orchestra model we will maximize ticket revenues by offering variety. In the past success came from making one highly homogeneous group of people happy all of the time. In the future, success will come from giving lots of different audience clusters the opportunities to get exactly what they want some of the time.

Finally, I would suggest that for both marketing and programming purposes we must understand our audiences much, much better than we have in the past. Dividing ticket buyers into “subscribers” and “single ticket buyers” and treating everyone within each category similarly just will not cut it anymore. We need to become as sophisticated as big corporations in understanding our customers’ behaviors.

Fundraising

While the model for how an orchestra should sell tickets may be becoming more dynamic and much more complicated, there are still best practices to be emulated. I am not sure that it really makes sense to talk about any single model for how an orchestra should raise contributed income. To the extent that we’re still subscribing to the “Culturally Aware Non-Attenders become Single ticket buyers who become Season Subscribers who become Small Donors who become Major Donors who leave us in their will” model we need to recognize that people on the margins don’t behave like people on average, and that there are plenty of good prospects to support the orchestra at a significant level who are never going to choose to become a season subscriber.

As I suggested yesterday, economic-cycle issues aside, there appears some communities where what has worked in fundraising in the past continues to work today. On the other hand, it is hard to avoid concluding that, in other communities, even if the orchestra is doing flawlessly everything that used to get the job done, many traditional sources of funding will not provide the level of support that they once did. Orchestras facing declining access to corporate, foundation, and government funds are increasingly dependent on major gifts from individuals. There is nothing inherently unsustainable about this strategy—individual donors are by far the single largest source of philanthropic donations in the United States. But it seems that many orchestras are now in a pattern of relying on a sequence of substantial “extra” gifts to fund annual operations, rather than to build endowment or fund extra initiatives (what I call “Bridge to Nowhere” campaigns). It is not hard to see that this is risky as a long term strategy.

Governance and organizational structure

As in fundraising, it seems to me that there is no single right model for how an orchestra should be structured, although there are clearly some wrong ways.

- Orchestras may not be a three legged stool, but they clearly cannot thrive without strong and committed volunteer, administrative, and artistic leadership.

- Orchestras where key constituencies can have candid dialogue about and strive to reach consensus on priorities and goals will be better able to survive and thrive.

- We need really smart and creative and committed people marketing, fundraising, and programming for orchestras, but all the imagination in the world won’t help us if our staffs don’t execute as well as our musicians do onstage.

- Volunteerism is changing in America—to the extent that years of demographic trends working against orchestra volunteerism have led us to scale back the ways in which we ask our volunteers to help, the upcoming spurt in newly retired baby boomers may provide opportunities to rethink how volunteers can help many orchestras, especially smaller budget organizations.

Regardless of what model of board involvement you subscribe to, ensuring that adequate resources are available to fund whatever scope of activity the board has approved remains a central part of the board’s job. There may be some communities where fundraising can be completely staff driven, but I would suggest that in most communities the board needs to be both leading by example, and asking their peers to follow their example.

Conclusions

Let’s conclude by asking what do we mean by model, anyway? Are we looking for an “exemplar,” a prescription for what an orchestra should play, and how it should sell tickets, and how it should raise money, and how it should operate, that guarantees success? Or are we looking for a simplified concept of an orchestra, one which tells us key issues to be addressed without pretending to dictate exactly how each of those issues should be addressed? Or are we simply looking for a learning tool, a better way to understand that mysterious, strange, wonderful, frustrating, inspiring entity which is the orchestra?

On balance, I would suggest that

- in many ways the traditional model focuses on the right things, and that

- there are still basic building blocks which an orchestra can implement which will help to address those things effectively, but that

- the environment in which we operate has become sufficiently dynamic and complicated that we should abandon the idea that there is any “simple” model which captures what an orchestra needs to do to thrive, and that

- every community is different, and every orchestra needs to make its case for community support within the context of the resources, aspirations, and priorities of its own community.

Obviously, there are lots more that could be said on all of this, but I’ve already gone well over my word count from Drew. So I’ll wrap up and hope that what I have said will provoke some discussion…

Very well said!

I would like to add to the discussion concerning the “three legged stool”, audiences, and social media an “Aha! moment” related to me by a musician in a regional orchestra.

He was subbing as concertmaster in Scheherazade and thought to invite his friends (and students) on Facebook and in a few cases through phone calls. More than 20 showed up and bought tickets at the door. Most came to the front of the hall to wish him well before and thank him afterward.

He was simply amazed at the response and has begun an effort to get others in this very traditional union orchestra to try it themselves.

The old model of compartmentalization in audience development (“It’s not my job.”)is hopefully on its way out in this orchestra in favor of a much more powerful and personal interaction.

This is such a well spoken cogent argument and I agree 100%. I find it ironic that those wishing to dismantle the traditional regional orchestra model in favor of a smaller more managable orchestra, are exactly those that need to do there jobs better. As an orhcestra member, I have always been in favor of and willing to volunteer to help with fundraising, even being outside of my “job description”. All any musicians I know of, including myself, have ever wanted and expected is to have upper management leadership to perform as well as we do onstage, meeting us halfway. However, often that isn’t the case and sadly rather than a higher standard for and from our leadership, they choose the easy way out by trying to get rid of us all together. Sad.

Teachout’s original article first enraged me, then inspired me to chuckle sardonically: following his logic, eliminating regional orchestras because of dvd’s and the iPod etc. is the same as giving up eating because you can watch reruns of Mario Batali making risotto, or Bourdain teasing his jaded palate with street food in Calcutta.

But, Curt: quite brilliantly stated! I’m especially intrigued by the formulation that programming has to appeal more to variety so that different “audience clusters” get exactly what they want.

Anyway, I’m going to share your posts with colleagues in Europe.

Interesting discussion but some of the finer points of where orchestras find themselves has been missed.

True enough that new approaches embracing changes such as social media and internet distribution channels have to be combined with traditional “blocking and tackling”.

But this does not address some of the fundamental changes that have occurred over the past 30 years and deepened during this Great Recession.

Without going into detail, here are some of the fundamental shifts as I see them:

> Changing demographics within the US (move to Sun Belt out of Rust Belt) Hence Cleveland Orch has to look to Miami to make a 52 week season.

> Global economic shift from US to China. Follow the money. It won’t be long before Chinese orchestras start poaching US players and sign the top conductors.

> Malaise of US education system and specifically music ed. I won’t beat this dead horse.

> Lack of flexibility of orchestra musicians content with long term CBAs to understand the realities of the situation and their role in the death of the Golden Goose.

> Lack of a healthy management/labor relations only equaled by the automotive and airlines industries. And look at where they are.

The reality as I see it is that while regional orchestras are a necessity for any community that wants aspires to provide its citizens a cultural life, few can sustain an orchestra that gives full-time employment to its musicians.

That’s just a fact. Being a musician, I wish it were different but it isn’t.

Up until the mid 1960’s even musicians in the Big Five orchestras held other jobs or made a large part of their income through teaching.

It is unrealistic to expect communities, esp in this economy with unemployment “officially” at 10 percent (not including the disenfranchised) that most US orchestras can sustain themselves at past levels.

That orchestra managers and their boards gave in to bargaining demands that could not be sustained in poor economic times is unfortunate.

The next ten years are going to be very hard for all US workers and orchestra musicians will not be immune to what workers in other industries are experiencing.

While I agree with most of what you say, I’m baffled as to why you’re leaving the “product” out of the “model” – namely, the musicians, guest artists, and music directors. These expenses typically add up to 50%+ of an orchestra’s budget. Even if you get everything “right” (whatever that means) on the administrative side, if half of the organization’s budget is out of control, the savviest marketing and fundraising won’t be enough.

Another aspect to the musician part of the model is the union. The fact that, ultimately, the musicians are not governed by the administration is a huge component of the business and part of the reason why orchestras are slow to change. (Hard to shift programming/scheduling strategies in the middle of a 3-yr contract.) If I, as a staff member, leak a story to the press, start failing in my job, or treat my co-workers with contempt or yell and swear at them, I most likely will be fired (and rightly so). Not so for unionized musicians. And that’s just the tip of that iceberg…

There’s plenty of blame to go around when discussing what’s gone wrong in the orchestral field and how it should be fixed. We’ll continue to spin our wheels if we only focus on one side of the issues.

I think Stephanie is right to focus on the total picture, but to place blame on the union is way too easy to do. First, I do not think anyone could argue that major orchestra musicians are paid anywhere near their worth (training, experience, and community value) compared to sports figures, movie actors, corporate CEO’s and the like. Second, in the market I live in, it appears fairly easy for union orchestras to rid themselves of musicians they wish to can, union or not. And third, the musician budget is hardly out of the control of administration. The union can have strength in their demands, but boards do not negotiate from a stance of weakness, either.

I read this discussion because I have been thinking recently about why I no longer take season tickets for our local (chamber) orchestra and indeed rarely attend concerts. As I live in a rural area of Ireland and have no formal musical education, my comments may have limited relevance, and at most I can comment on the “Audiences” part of the model, but here goes anyway.

I’m not wealthy enough to be a Patron or suchlike, and the social aspect (“but we always meet our friends at the Friday concert”) didn’t appeal, but I did buy season tickets for several years. When I found that I wasn’t attending concerts for which I had already paid, I reconsidered my support.

For me, the music is what matters. My musical education is not sufficient for the conductor’s interpretation, or the standard of playing, to drag me out on a cold winter’s night, but I am interested in hearing music I haven’t heard before. Beethoven? It’s cheaper to buy a CD, which I could listen to again and again — but I still remember the effect that a touring Dutch youth orchestra made on me with its performance of “Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten”, and I have been grateful to them ever since. On the other hand, the Irish National Symphony Orchestra visits the area once a year, but the programme is so depressing (assembled from such familiar pieces) that I never attend.

I don’t intend to suggest that orchestras should base their programming entirely on 20th and 21st century music, but I think that, as Galen Johnson says above, programming has to appeal more to variety. The answer is not to include a single C20 piece in a concert of romantic music: it is to provide a concert of romantic music one week and a concert of C20 music the next. And if the second calls for smaller (or different) forces from the first, even if it uses one electric guitarist instead of thirty fiddlers, then so be it.

bjg