Who determines how much a musician earns in overscale, the part of a musician’s individual agreement that deals with extra wages paid over and above the minimums guaranteed by the collective bargaining agreement? Is it the CEO, music director, the board, a combination, or none of the above?

If nothing else, Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) principal flute Elizabeth Rowe’s lawsuit alleging sex-based pay discrimination is providing ample pretext for learning more about that very process and the roles key leadership figures play.

First and foremost, it’s important to understand there are no best practices when it comes to when, if, and how music directors (MDs) become involved in the negotiation process.

When they do become involved, it’s typically at the behest of the executive and to quantify value. “[Musician X] is asking for [$Y], is s/he worth it?”

Having said that, I’ve been involved in negotiations where the MD played a crucial role in non-financial decisions such as, but not limited to, granting early tenure, immediate tenure (rare, but happens), or guaranteed concerto performances.

Beyond that, it’s all personality driven. Some MDs are loathe to get involved while others insert themselves as much as possible.

One consistent variable is MDs have no formal training with compensation standards and practices.

Depending on the situation, this can be a good or (very) bad thing for either party in the negotiation.

When it comes to making the final decision, it almost always comes down to the CEO/Executive Director.

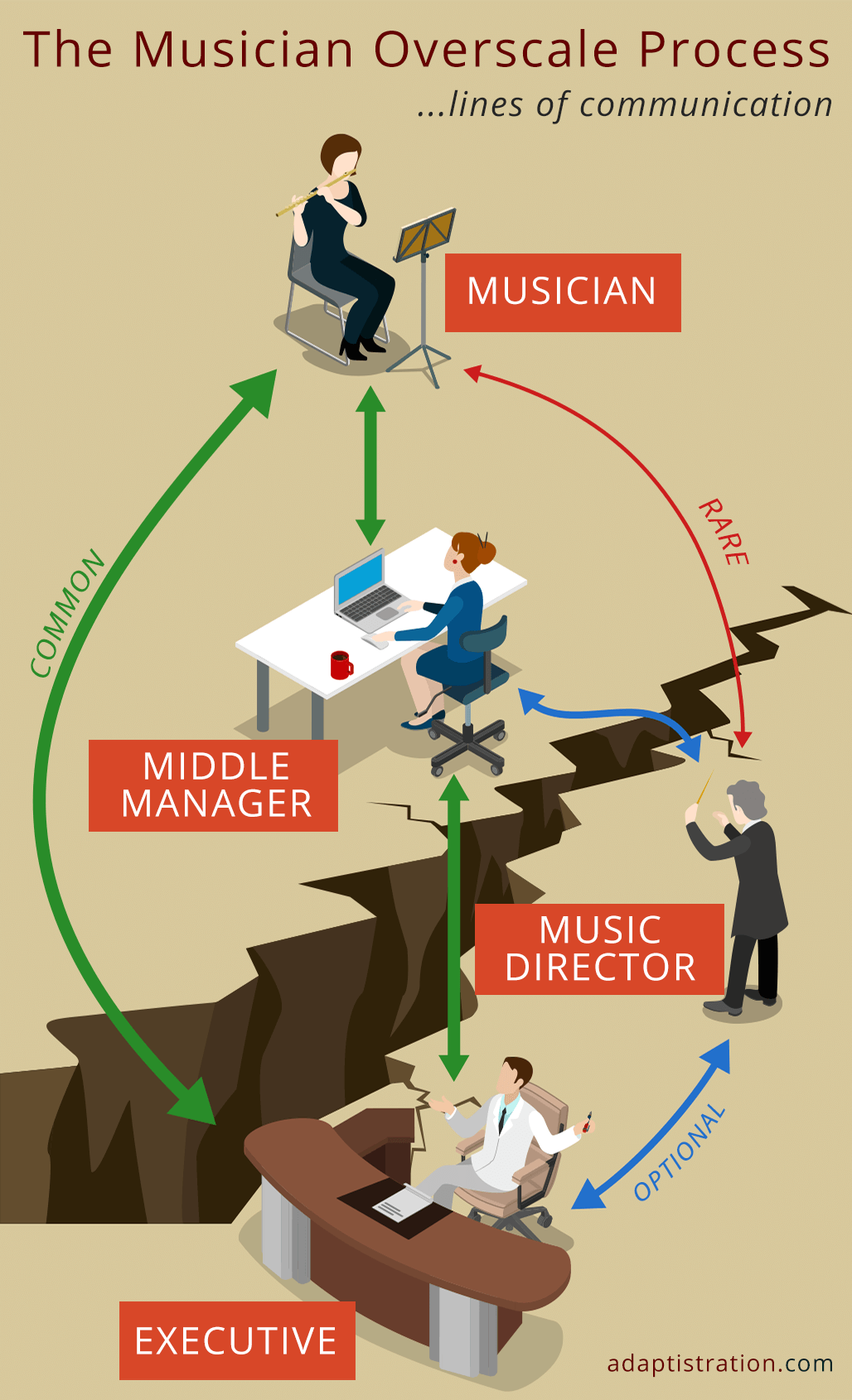

Since this is one of those scenarios where a diagram goes a long way, I put together a quick infographic to illustrate the lines of communication during a typical overscale process.

Common Communication Pathways

- Musician and Executive communicate directly.

- Musician negotiates through a middle manager, but the Executive still makes the final decision.

As an aside, outside of cases where the executive is ill-tempered or ill-suited to negotiate (it happens more often than you may think) the first option is preferable. It saves everyone time and goes a long way toward building clear working relationships.

Having said that, I’ve witnessed a steady rift growing across orchestras of all budget levels where the executive is handing off this work to a middle manager. Hopefully, this is an anomaly and not the new normal.

Getting the MD Involved

Typically, the employer will reach out to the MD with specific questions but there’s nothing preventing MDs from acting proactively.

Outside of situations where one or more parties is playing games, MD involvement is useful in that it provides clarity surrounding issues outside the executive’s area of expertise, such as confirming artistic excellence or comparative value with existing ensemble musicians.

Rare, But Powerful, Influence

It isn’t common for the musician to communicate directly with the music director; but when it happens, it usually produces profound results. current

Assuming the MD doesn’t shut down communication at the onset, making him/her aware of the impending/existing negotiation all buy assures s/he will get involved.

The stories I could tell…but won’t.

Suffice to say, the MD can be a valuable weapon for a musician but like all weapons, they should be willing to accept risks involved with the potential for backfires. As one of my mentors used to say, “don’t throw a stink bomb when you’re standing downwind.”

Ideally, the field would begin to pursue a policy of compensation standards and practices that not only helps marginalize sex based discrimination, but provides routine training for MDs and institutes a process that expects their participation.

Until then, we’ll have to continue making do with this ill-fitting suit.