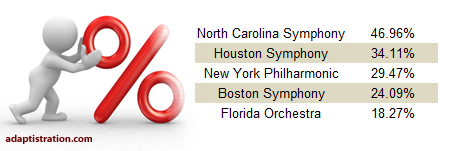

Although the 2006/07 season didn’t bestow the average ICSOM music director with outlandish improvements in compensation, many of these stakeholders managed to set all time high compensation levels at his/her respective organization. Moreover, one conductor set a new record for the entire field with an annual compensation totaling nearly $3,000,000…

WHERE THE DATA COMES FROM

In order to provide information that is as accurate as possible, data from the 2006/07 season is gathered from the following sources:

- Music director compensation figures were obtained from their respective orchestra’s IRS Form 990 for the 2006/07 concert season.

- Total expenditures were also obtained from each respective orchestra’s IRS Form 990 for the2006/07 concert season.

- Base Musician compensation figures were obtained from records collected by the American Federation of Musicians and International Guild of Symphony, Opera, and Ballet Musicians (Seattle) for the 2006/07 concert season.

Adaptistration makes no claim to the accuracy of information from documents compiled or reported by external sources. If you have reason to believe any of the information is inaccurate or has changed since reported in any of the above sources and you can provide documentation to such effect, please feel free to submit a notice.

WHAT THE NUMBERS DON’T SHOW

It is important to remember that the numbers shown do not always convey a complete compensation picture. For example, a music director may have had a large increase in salary due to leaving a position and per terms of the employment contract, may have received a sizeable severance or deferred compensation package. As such, the cumulative compensation may artificially inflate annual earnings.

Furthermore, these figures may not reflect bonuses or other incentive payments, therefore underreporting what conductors may actually earn nor do they include combined salary figures for conductors serving as music director for more than one orchestra. Also missing from the figures are expense accounts and other perks; as such, the cumulative compensation for music directors may or may not be more than what is listed. Additionally, the documents used to gather data do not indicate how much of the season an individual received a salary. As such, excessive adjustments in the percentage change from the previous season’s compensation may be artificially adjusted.

Although the music director compensation figures include the combined amounts reported as what the IRS classifies as “compensation” and “contributions to employee benefit plans & deferred compensation,” each orchestra does not always report figures for the latter category. Additionally, some organizations list music director compensation among the five highest paid private contractors as opposed to employee compensation. In these instances, no information about benefits or deferred compensation is available.

The Base Musician compensation figures do not include any additional payments including but not limited to outreach services and minimum overscale and/or seniority payments. Finally, these figures do not include any of the opera, ballet, or festival orchestras which are members of ICSOM or IGSOBM.

NEW FEATURE: REAL AVERAGES

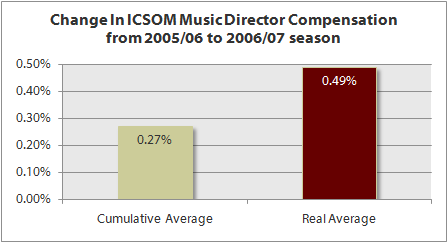

To date, each year of the Orchestra Compensation Report has provided overall increases and/or decreases in average compensation; however, those figures don’t provide an entirely accurate picture. For example, factoring in compensation data from orchestras that did not pay a music director for an entire season or paid an incoming and outgoing music director in the same season can easily skew that average up or down. As such, this year’s report introduces the average change in compensation from one season to the next using “real averages,” which are based on figures that filter out incomplete compensation records.

In some cases, periods where orchestras are without a full time music director can have a significant impact on the overall averages. For example, in the 2006/07 season, one of the perennial Top 10 highest paying organizations, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, did not have a full time music director. To give you an idea of how this music director gap influenced the overall averages, if you factored in the previous season’s salary into this season’s figures, it would have moved the overall average from $607,065 to $654,123.

Consequently, when the real average filters are applied to all music director compensation figures for the 2006/07 season, the data indicates that the average conductor serving a full season of employment experienced an average increase in compensation that was nearly twice as high as the overall average (although still below a full percentage point), as illustrated in the chart below.

TOP EARNERS AND QUICK FACTS

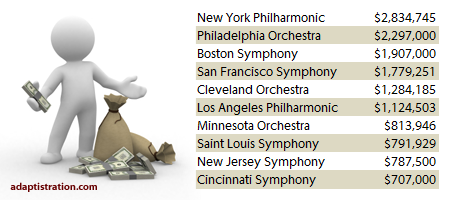

- Compared to figures from the previous season, even without the inclusion of a Chicago Symphony Orchestra music director salary, the average compensation for the Top 10 highest paid music directors increased by 2.47 percent.

- Cumulatively, the Top 10 music directors earned $14,327,059 (which excludes any compensation from orchestras outside those in the Top 10), which is higher than the total expenditures for nearly half of the ensembles in this group.

- The New York Philharmonic’s music director set a new all time high compensation level at $2,834,745 which is nearly eight percent higher than his previous record in the 2004/05 season of $2,638,940.

- Two conductors managed to exceed the $2 million mark this season, something which hasn’t happened since the 2004/05 season.

Now More Than Ever

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the debate over the validity of music director compensation levels won’t end anytime soon. At the same time, many arguments for and against those levels is sound but given the financial condition of many orchestras, two items worth heightened consideration stand out more than ever:

- Quantifying return on investment: one of the strongest points supporting current levels of music director compensation is any individual is worth what he/she brings to the organization. The trick here, and this is where most groups fall short, is whether or not sincere efforts are made to quantify this value. In particular, what sort of artistic benchmarks are in place and is the music director directly tied to fundraising accomplishments. Ultimately, an orchestra’s board is responsible for providing verifiable corroboration of annual goals for each of these points and in times such as these where executive salaries are perceive with anything but a presumption of innocence, they should be offering up that info without being asked (think PRs and the annual report).

- Comparative parity: Although a number of music directors are complying with requests for temporary reductions in compensation during periods of strained cash flow, it is important to realize that some of the orchestras in this group hover at or below base musician salaries capable of sufficiently providing minimally satisfactory living conditions (especially for those with spouses and children). Consequently, there is a sincere difference between the impacts of a music director that accepts a double digit cut that reduces an already large salary to a lower, but still large, level as opposed to an identical percentage cut for a musician that results in moving him/her below the minimally satisfactory living conditions threshold. In cases such as these, the board needs to consider these dynamic variables when determining appropriate levels of comparative parity and take proper action.

1 thought on “2009 Compensation Report: ICSOM Music Directors”