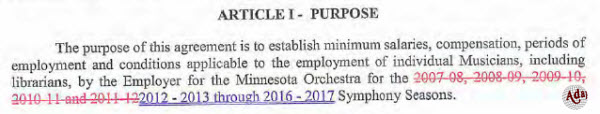

This installment of our ongoing examination of the Minnesota Orchestra Redline Agreement (MORA) will focus on proposed changes to Individual Contracts. All things considered, Individual Contracts are a mystery to just about everyone outside of those directly involved. Consequently, let’s change that by shedding some light on how all of this works then jump into examining the related MORA propositions.

Introduction Material

If you’re new to this series, please take a moment to expand this content which explains what a redline contract is, the ground rules for this examination, define related acronyms, and the overall goal of the series. You’ll also have an opportunity to download a complete copy of MORA.

However, if you’ve been following along since the onset, feel free to skip ahead.

Professional Disclaimer

Over the past two decades, a sizable portion of my consulting work has revolved around individual contracts. My position is a bit unique in that I work on both sides of the fence; meaning, I represent both musicians and managements (although the latter is related to providing counsel and conducting research).

Since all of my work in these matters is conducted under strict non disclosure agreements, I will not be providing direct examples. Nonetheless, my work has involved securing terms for more than 100 concertmasters, principals, assistant principals, associate principals, and fixed chair section musicians in the largest budget orchestras down through those with annual budgets of a few million dollars.

An interesting side note here: individual contracts are quite similar to the individual employment agreements crafted by orchestra executives that define not only base compensation but the array of benefits and perks above and beyond the minimum package offered to all administrative employees.

The preparation, method, and process (sometimes better defined as posturing) involved is nearly identical to the way individual musician contracts are crafted. Having worked for executives seeking to secure terms, boards seeking to get executives to work for less, musicians seeking improved terms, and executives tasked with minimizing overscale costs, I can firmly attest to an abundance of ironic similarities in the process regardless which parties are involved.

Individual Contracts Defined

Individual Contracts, also referred to as overscale contracts, are employment terms negotiated between an individual musician and the employer. Here are some key points to keep in mind:

- They do not supplant terms specified in the collective bargaining agreement.

- They may not contradict terms in the CBA and musicians with individual contracts are afforded all of the same protections and are responsible for all of the same duties and responsibilities as defined in the CBA.

- An employer is under no obligation to offer or provide for individual contracts except in instances where minimum overscale terms for specific orchestral positions are defined in the CBA (more on that below).

- Monetary terms are typically defined by dollar value and not by percentages over and above the base scale, except in instances where minimum overscale terms are defined in the CBA.

- There is no universal formula for determining individual contract rates and the amount orchestras allocate to this expense varies wildly amid groups in the same budget class as well as those in different classes (oh, the stories I could tell).

- Musicians may negotiate for monetary and non-monetary terms.

- Individual contracts may have fixed or “evergreen” terms.

- Some organizations allow individual contracts to be negotiated or renegotiated at any point where others create specific windows of opportunity.

- Some organizations require musicians to negotiate directly (meaning, they prohibit the use of outside negotiators) while others have no restrictions.

- When bargaining for individual contract terms, anyone from the executive administrator down through a mid level operations manager may represent the association; however, final terms are typically approved by the executive.

- Music directors and board members are not actively involved in the bargaining but his/her opinion regarding the musician involved can have a great deal of influence in the outcome. Likewise, it is typical for management to confer with the music director in order to determine the value of any given musician.

Simply put, there’s no prescribed method for arriving at optimum individual contract conditions; instead, terms are determined more by individual tenacity, competition, accomplishment, and the respective organization’s labor culture.

In order to acquire a clear understanding, it’s critical to point out that some orchestras set fixed parameters for monetary terms (especially middle and lower budget groups); meaning, an individual musician can negotiate up to, but not past certain caps. Similarly, those parameters can provide a minimum starting point for overscale but not place any caps. In short, the sword can swing both directions.

However, it’s worth pointing out that mandated overscale defined in the collective bargaining agreement is typically restricted to monetary compensation and individual musicians are still free to negotiate non-monetary terms, some of which incur no costs to the organization.

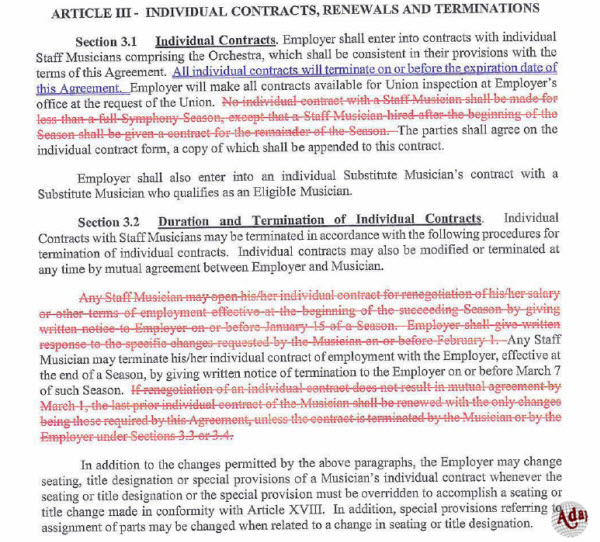

Article III; Section 3.1 and 3.2

Quantitative Summary

Language acknowledging the existence of individual contracts is quite common. In some cases, it is a simple sentence or two indicating requests for individual contract terms are or are not entertained and if so, the related conditions. In most cases, it’s common to provide some parameters such as periods when bargaining may or may not occur, such as a prohibition during active CBA bargaining.

The most profound change in the MORA proposal is the addition of language that terminates all individual contracts by September 17, 2017 or earlier for any agreements with fixed expiration dates occurring before that threshold.

Although the MORA proposal doesn’t prohibit individual contracts, it is clear that the orchestra intends to trim back on the quantity and/or quality of terms. This is evidenced by the removal of a provision in Section 3.2 that requires the MOA to honor the terms of an existing individual agreement should both parties fail to reach mutually agreeable terms during any subsequent renegotiation.

Other proposed changes include removing deadlines for both parties to provide terms and official replies. The only language to remain unchanged is related to the termination individual contracts.

Management Perspective

On face value, the rationale for including language that guarantees the organization will shed itself of individual contract terms while simultaneously proposing steep cuts to base pay seems self evident. Since most individual contracts define dollar values as opposed to percentages over base compensation, the need to remove any language that protects those terms would be critical unless the cost differences have been accounted for by increasing the earning gap between musicians on the top and those earning entry level wages.

Eliminating guarantees for renegotiating existing individual contracts only increases the likelihood that the only time a musician will ever be able to bargain for individual terms is at the point s/he is hired and/or receives tenure. This would produce much lower long term costs as well as prevent any musician from attempting to leverage an offer from a peer orchestra for the purpose of securing better terms to remain with the ensemble.

Musician Perspective

For employees assuming duties and responsibilities that exceed those of standard members, individual contracts are the only option for generating additional benefits that acknowledge those contributions.

Consequently, the musician perspective is comparatively cut and dry and it provides freedom for those key musicians to obtain a degree of acknowledgement and recognition for their role.

Again, it’s fair to point out that generalities on these matters shift from one budget class to the next but for a group the size of the Minnesota Orchestra, it is almost unheard of for the musicians to adopt measures via the CBA that would limit or otherwise cap individual contract terms.

Observations

Although the proposed language in this section of MORA may seem like a straightforward effort to reduce overall costs, it also contains the potential to produce a considerable amount of dynamic consequences; not the least of which includes:

- Increased workload. Unless the MOA is planning to deny most individual contract requests out of hand, they can expect an increase in the number of musicians initiating bargaining demands. Likewise, removing some of the existing protections (such as continuing previous conditions if new terms aren’t mutually agreeable) can actually work against management in that it decreases employee complacency. As a result, the organization can expect an increase in the number of bargaining requests along with a higher degree of antagonism.

- Increased turnover. Regardless of how much talk exists about an oversupply of musicians, that hasn’t made a noticeable dent in individual contract terms and overscale. Orchestras continue to struggle to attract and retain key artistic employees. By removing the ability to renegotiate terms mid-contract, the MOA would position itself as a very “poachable” ensemble.

- Decreased quality. Although musicians tend to be fond of defining an organization’s overall attractiveness by the level of base salary, that’s only accurate in an applicable sense for smaller and mid budget size orchestras. The larger the budget, the more individual contract terms impact an orchestra’s artistic gravity. In short, do you really think it matters to the potential principal oboe if Orchestra A’s base salary is three percent less than Orchestra B? Not a chance; instead, it is individual contract terms that end up tipping the scales.

- Guaranteed cyclical bargaining. By proposing the term “All individual contracts will terminate on or before the expiration date of this agreement” without an indication that the term applies solely to the 2012-2017 agreement, existing and incoming musicians eligible for individual contract improvements can expect those terms to be terminated at the end of every CBA. Thus initiating the individual contract bargaining cycle from scratch along with each new CBA, not to mention adding another layer to the “increased workload” point above.

In Closing

It is worth noting that when negotiating monetary terms for individual contracts; managers typically refuse to link overscale payments to base compensation as well as resist terms that include minimum percent increases from one season to the next.

Traditionally, this provides a degree of insulation over ancillary increases in overscale expenses since base compensation rises at more or less steady rates; while individual musicians are less likely to engage in bargaining for new terms once their initial individual contract is settled.

In an ironic twist, this approach works against the MOA and it serves as reasonable grounds for why MORA contains what might be considered counterproductive Individual Contract terms. If the organization had linked individual contract monetary terms as a percent over and above base salary, they would have been guaranteed parallel cost controls for whatever terms the musicians ultimately accept.

Assuming the MOA’s goal isn’t to deliberately hasten the turnover of key musicians, unilaterally dissolving all overscale agreements via CBA decree is a high risk approach to dealing with what the organization defines as long term financial problems.

In the end, this peek inside the much larger proposal will prove to be a useful when developing your own practical on the dispute. In the meantime, if you have any questions about individual contracts in general or the MORA proposal, send them in via a comment below.

2 thoughts on “Examining the Minnesota Orchestra Redline Agreement Part 2”