Today’s article will examine some of the unique components of the Columbus Symphony Orchestra (CSO) maser agreement (also known as a collective bargaining agreement or “the contract”) governing full time and per service musician employment. We’ll also finish up the remaining few questions with CSO Executive Director, Tony Beadle…

When it comes to master agreements “flexibility” is a popular buzzword among orchestra managers. In particular, it refers to any contract language which is less specific or contains provisions allowing the organization to temporarily suspend contractually mandated responsibilities. These can include everything from the minimum number of musicians employed to the minimum number of hours required between back-to-back services (rehearsals/concerts); the fewer specific requirements a contract specifies, the more “flexible” it is. In some cases, although fewer on average, musicians deliberately seek flexible language.

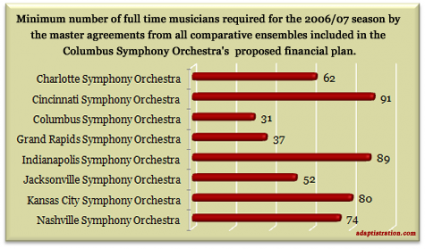

Compared to other International Conference of Symphony and Opera Musicians (ICSOM) ensembles, the CSO’s master agreement is one of the most flexible with regard to employment language. For example, the CSO has one of the smallest numbers of required full time musicians of any ICSOM orchestra, as illustrated in the chart below.

Nevertheless, the CSO’s proposed financial plan calls for reducing the number of full time musicians from 53 down to 31. This may seem contradictory, but it isn’t. Instead, it is a perfect example of the flexibility already built into the CSO’s master agreement. It is true that the CSO currently maintains 53 full time musicians, however, only 31 of those positions are provided for in the master agreement by instrument.

The remaining 22 positions have been added via a flexible provision which allows the orchestra to grow full time positions slowly and only transfer them over to “core” positions as the organization secures ongoing financial support. For example, 15-20 years ago the CSO maintained 60 full time musicians but that number was reduced to 53 via the clause in the maser agreement which does not require the CSO to maintain positions outside of the core 31 which are vacated through attrition.

As such, this information allows the remainder of Tony Beadle’s interview to make more sense. For you reference, you can download a .pdf copy of the CSO’s financial plan at their website (a direct link is unavailable as the CSO website is designed entirely in Flash).

Drew McManus:

Although the financial plan calls for a reduction in full time musicians to 31, the number of full time musicians required by the current collective bargaining agreement is 31. Could you explain why the plan is calling for something which already exists via the collective bargaining agreement?

Tony Beadle: What he board is asking for is those musicians who are not currently included in the [minimum number of full time musicians per the current master agreement] to be immediately moved to per service status.

Drew McManus: According to page 29 in financial plan, the organization wants to reduce the number of full time musicians down to 31. How does the organization propose to select which musicians need to be downgraded?

Tony Beadle: Those with full time contracts who are not provided for in the contract.

In particular, the full time positions provided for in the contract Tony is referring to include: two (2) Flutes, two (2) Oboes, two (2) Clarinets, two (2) Bassoons, four (4) French Horns, two (2) Trumpets, two (2) Trombones, one (1) Tuba, one (1) Timpani/Percussion, one (1) Harp, five (5) titled Violins, two (2) titled Violas, three (3) titled Cellos, and two (2) titled Basses. Consequently, all other full time CSO musicians occupy positions which the CSO board of directors has proposed to move to per service status at the conclusion of the current master agreement in August, 2008.

The proposed financial plan does not contain any information about how the organization proposes to implement the reduction in full time musicians beyond mentioning that it will be addressed in upcoming collective bargaining agreement negotiations. However, since the current master agreement provides considerable flexibility with regard to full time positions vacated through attrition I asked Tony if the organization had explored any options that would allow for musicians to leave on their own volition as opposed to the conflict which is bound to arise from forced demotions.

Drew McManus: Did the board of directors ever consider less confrontational options than immediate demotions when designing the proposed financial plan such as offering incentives to the remaining full time musicians to vacate positions at their own volition?

Tony Beadle: The board has not considered that option but as I’ve mentioned, we’re willing to re-examine the strategic planning process and everything in that respect is on the table.

Finally, the flexibility in the CSO’s master agreement is not restricted to full time musicians. Instead of providing a firm number of minimum service guarantees, as the vast majority of ICSOM orchestras do for their per service musicians, the CSO master agreement allows the organization to control musician expenses via a per service formula. In particular, the organization can reduce musician expenses by as much as 10% per season for each musician with no less than three years worth of service while those with less have no guarantee formula. The exact language states:

“Each Per-Service Musician (who has averaged 100 or more services in the immediately preceding three (3) seasons as a Per-Service Musician) shall be offered a minimum number of services to equal at least ninety percent (90%) of the average number of services offered [that Musician] in each of the three (3) immediately preceding seasons with the Orchestra. The qualifying Musicians shall be offered the required number of guaranteed services in their individual contract. Non-qualifying Musicians shall not be guaranteed any minimum number of services.”

We’ll examine how all of this inherent flexibility interacts, and in some cases conflicts, with provisions from the CSO’s proposed

financial plan in upcoming articles.

For an ICSOM orchestra, I am sad to see that Columbus does not consider principal percussion its own separate position.