I’ve had a number of requests for a copy of my TEDx presentation on labor relations and the arts so I wanted to take a moment today and post the slides along with the script. Since I used an iPad teleprompter app, the actual presentation was pretty much verbatim; as such, this should provide a very clear idea of what transpired…

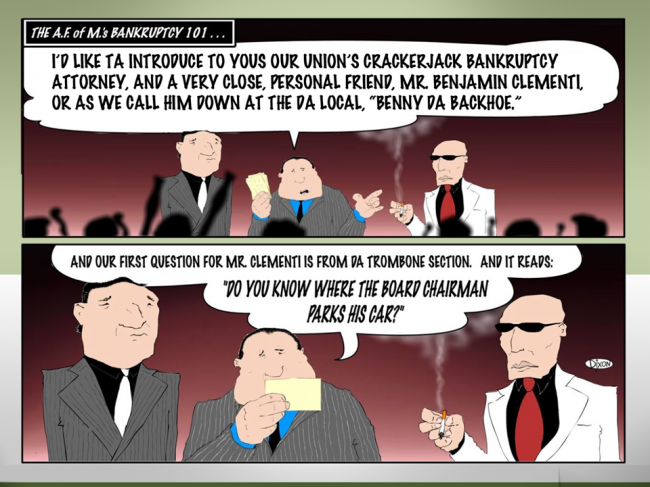

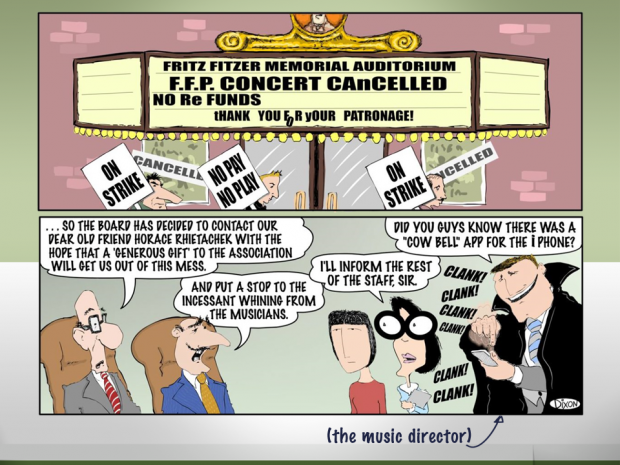

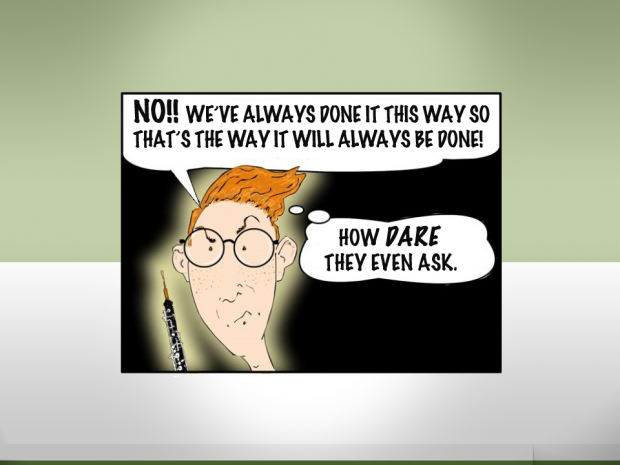

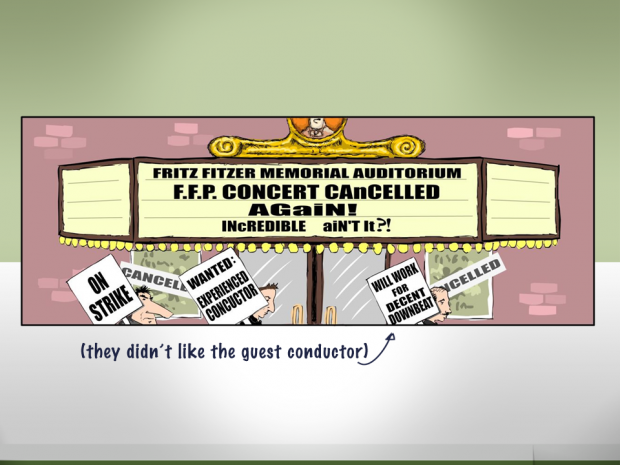

Before we jump into everything, I want to point out that all of the cartoons in the presentation are from Who’s Minding The Score?, Adaptistration’s very own weekly cartoon strip on orchestra life. I want to express my sincere thanks to Dixon for going above and beyond to help out via colorizing many of the older black and white versions (the Hendrick’s is on me Dix!).

Labor Relations & The Arts

By Drew McManus, delivered 5/7/2011 for TEDx Michigan Ave

Let’s have some fun today. More to the point, let’s have some fun with labor relations.

I know, I know; the idea of having fun with something like labor relations amidst one of the worst economic downturns since the Great Depression might seem like…oh, what’s the word I’m searching for; counterproductive, disadvantageous, impractical, good-for-nothing, worthless?

Well, we’re going to take this to a worthwhile place by applying some industrial strength transparency to a process that is all but hidden from outsiders and even those on the inside are usually forced to view it through a semi-opaque lens. But it’s high time to point out that the Emperor isn’t wearing any clothes and in fact, should really have a doctor take a closer look at that thing on his back.

Sometimes, this makes people squeamish. Not the thing on the Emperor’s back mind you, but transparency. After all, labor relations only tend garner attention when people are hurling insults at one another and finding new and creative ways to apply logical fallacies. But the point is that the arts have become so comfortable with not having anyone really challenge their ideas about labor relations that even the faintest rays of transparency are met with stereotypical, almost cartoonish, reaction.

But the good news in all of this is people tend to take a step back and see things with a bit more perspective when you employ some satire and this business has no shortage of raw material to work with. There’s so much in fact, that when the opportunity to turn stereotypical cartoonish behavior into an actual cartoon crossed my path, I thought it was something worth exploring. And ever since then, it has been an enormously useful tool to hold up a mirror to some of the more egregious behaviors. It also helps illustrate my dream for the future of labor relations in our field and I’m going to use some of those cartoons to share those passions with you today.

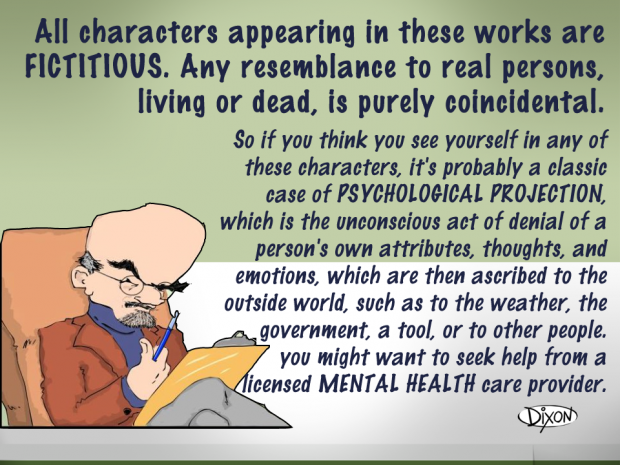

But before we begin, I’m required to read the cartoon’s disclaimer:

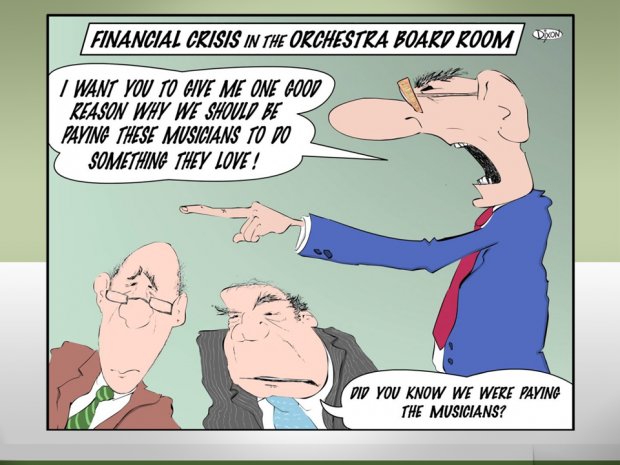

Let’s begin by reviewing what people think they know about stakeholders, which for this exercise includes board members, administrators, and artists. Here’s a stereotypical view that continues to pop up in some of today’s mainstream media:

As over the top as this appears, it’s an actual statement from an orchestra board chair. One of the dirty little secrets inside the field is the people legally entrusted with the authority to make the final decision and act as stewards of public trust are the least knowledgeable people about how the arts really work, who artists are, and how all of this fits into their community.

Ironic, isn’t it?

But it also goes a long way toward pointing out one of the larger cracks in the labor relations foundation in that it is all too common for stakeholders to view labor relations as focusing primarily on interaction during active bargaining cycles. When combined with the ironic nature of board involvement and increasingly detached artist participation, it doesn’t take long to create a vast gulf between the stakeholders at either end of the spectrum.

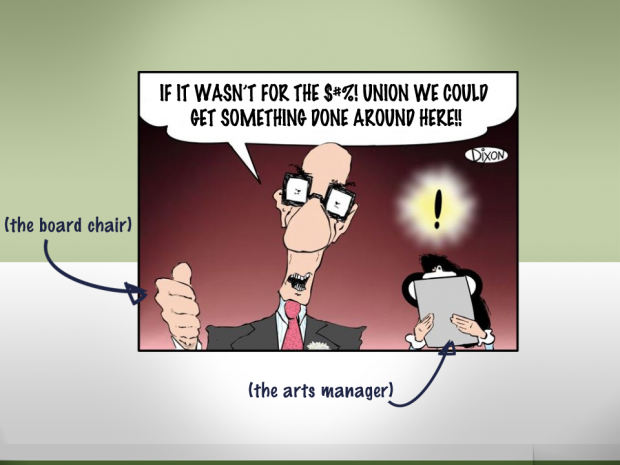

But at least our board chair caricature gets credit for calling the musicians “musicians” instead of employing the “U” word, unions.

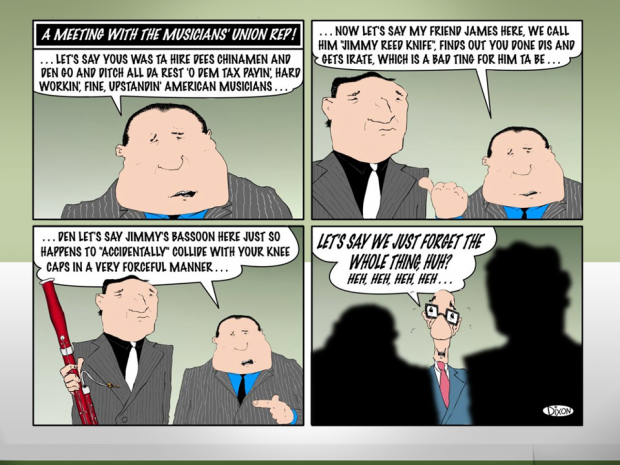

I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard sentiments along those lines during my consulting work when tempers start to run hot, albeit usually with a few more colorful metaphors thrown in. Its statements like this that point to one of the growing problems in a labor relationship and both end up in the same place, dehumanizing stakeholders. In those cases, you can almost see the following mental image in the mind of some board members and executives when they think about the union:

This is the point where a history lesson comes in handy in order to dispel some myths.

A long time ago in an era far, far away known as the 1960s, orchestra musicians decided they wanted to represent themselves during negotiations. Until that time, orchestra associations negotiated directly with the local union president, like the stout gentleman in our caricature, and those individuals looked at symphony musicians as some of the highest paid gig players in town so why bother pushing for anything else.

But the musicians finally won out and as a result, they have far more control over crafting specific conditions of their bargaining agreements as compared to the United Auto Workers. They get to select their negotiator, have elected representatives participate in all bargaining sessions, and ratify any proposal by a democratic vote.

Now, this system is far from perfect, but it means that the stereotypical image of guys who look like this controlling the artist labor pool couldn’t be farther from reality.

In fact, an organization’s artists have substantially more control over how working relationships evolve and negotiations unfold than any outside union influence. So if you hear someone complaining about union control, whether they realize it or not, they’re really talking about the artists.

So it shouldn’t come as a surprise to learn that when employers approach relationships with a “union overlord” stereotype in mind, all they end up doing is agitating their own artists. And things usually end up here:

If you look at the groups who are successfully managing debt, enjoying periods of stability, and in some cases amidst stages of legitimate growth, you’ll notice a few common traits such as mutual respect and high levels of regular stakeholder involvement; all with a lack of pretense. It also means they don’t make a point of going around telling everyone how much they respect one another, which by the way if you have to go around saying how much you respect someone, the reality is you probably don’t and what you should be saying is “we respect your input until it comes time to actually make our decision.”

So how does the labor side of the equation become unbalanced? Where does righteous indignation like this come from?

One of the real benefits following the big changes that transpired in the 60s via increased musician involvement in negotiations is the entire field enjoyed a period of unprecedented evolution. And by evolution I mean relationships grew. Old limitations were tossed out the window and everyone started filling in the new frontier.

The problem is that after time, too many organizations forgot that in order to maintain trust, it takes continuous effort. In short, people become lazy. For musicians, all of that on-the-job training related to relationship and trust building was slowly becoming a lost art. And to make matters worse, the one area where unions could have played a vital role by creating a series of sustained training programs that taught artists how to represent their peers between negotiation cycles, never fully materialized.

There’s no getting around the fact that they became complacent. The result was an increasing number of gaps in training new generations of representatives. Combine this with the unintentional result of increased professionalism throughout the arts administration field, which in turn never bothered to teach their students how to properly engage artists as stakeholders, and you have the foundation for the sort of hyper-dysfunction that pops up during the low point of economic cycles.

What’s important to realize at this point is there are no silver bullets to labor harmony. The best negotiation model is only as good as the people participating so in order to build a healthy labor relationship, we need to be honest with one another and have the courage to embrace transparency.

Speaking of transparency, let’s apply some right here and now and own up to what most of our labor troubles are really all about, regardless if it’s at the bargaining table, during strategic planning sessions, or right down to day-to-day working conditions.

First up is control.

Stop pretending that we’re not fighting over what we’ve been fighting over for decades: control. Employers want to be able to tell the artists what to do, when to do it, and how to get it done without any restrictions or feeling like they’re being held hostage to every last artist whim.

Artists want wage and benefits guarantees along with parameters placed on working conditions, lest they end up in a community engagement scheme like this:

Unfortunately, it’s become fashionable to take our fights over control and package them in boxes marked community engagement, structural deficits, artistic parity, or whatever jargon du jour is all the rage. In the end, regardless of how the fight settles, the core struggle over control continues to simmer. Even during periods of intense economic stress, we manage to find ways to interject unrelated control issues into a process as cut and dry as emergency wage concessions.

Talk about making a bad situation worse, it’s almost as though some in the field are compelled to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

In order to build a healthy labor relationship, both sides need to realize the struggle over control is expected and each individual organization will only find a sustainable balance between extremes once they abandon the goal of obtaining dominant control in the relationship.

Training.

Of all the issues involved in labor relations, this is the one where artists need to do the most work. And to be clear, I’m not talking about artistic training but the sort of training they need to be fair and responsible representatives and sincere, engaged institutional stakeholders. Increasingly, they become engaged only during active bargaining cycles and incoming representatives receive little to no training on how to function in their roles in the stead. As a result, stakeholder interaction has been reduced to some sort of cold war labor detente.

It should come as no surprise that committee service for artists is inspired far more by settling grudges as opposed to sincere stakeholder responsibility. Combine this with a complete lack of understanding about institutional history and you end up with committee members who focus efforts on the least important issues.

As of now, there are no major initiatives I’m aware of within the artist unions to reverse this trend. Training material, where available, is incomplete and woefully out of date and there are no dedicated human resources committee representatives can approach for advice and support for issues related to establishing and maintaining a healthy ongoing relationship with board members and administrators.

This final issue is perhaps the most sensitive of all but that is only surpassed by its importance: accountability.

It’s difficult to get over the idea that sometimes accountability means a referendum on you but sometimes, that’s the way the process unfolds. But I prefer to look at accountability as the driving force that maintains a commitment to ethics and values. As a field, the arts contribute to society not only through our mission statements, but through the exemplary way we conduct business in an environment that has little to no independent oversight. And the first step in that process is being accountable to each another.

Remember the irony about board members? This is where it moves from irony to tragedy in that far too often, the people charged with oversight and accountability are not in a position to properly carry out those functions. To a large degree, this gap had been filled in by artist stakeholders who were involved enough to launch credible demands for institutional accountability.

But the erosion of quality involvement has led to a chasm where calls for accountability have less authority.

The other unintentional byproduct of this syndrome is the field is no longer in a position to adequately recognize and reward administrators and board members who do an exemplary job. Instead, a culture of lowest common denominator drags down those who excel until a culture of mediocrity becomes the norm.

Ultimately, all of this has led to an operating environment that is becoming increasingly clogged with prolonged and vicious labor disputes that can perhaps best be summarized as being more about the fight than what both parties are fighting over.

Well, I can’t give you that prescription but what I want everyone here to leave with today is the knowledge that all of this can rapidly change for the better in very short order. We need to remember that winning a fight isn’t what a disagreement is all about. We need to let go of stereotypical outlooks and become better people who spend more time being straightforward with each other and building trust than we spend attempting to cover our real intentions with spin laden press statements.

We need to be people who care to be involved in the organization beyond the point of determining what goes into our paycheck. We need to create a culture that embraces and rewards transparency along with holding stakeholders responsible for their outcomes.

And we need to remember that in order to let each organization reach its full potential and be everything we dream it can be, we must share control and do our part to be better tomorrow than we are today.

It might mean fewer cartoons in the future, but it would be worth it.

BRAVO!

I wanted to come to this event! By the time I knew it was going on, flights from NYC were too expensive for my budget. Thanks for posting your presentation. I’m really hoping there will be video posted of the whole thing. Is that in the works, or just my fantasy. if the latter, I’ll be experiencing “kicking myself for missing it” syndrome for a while.

Too bad you couldn’t attend, it would have been nice to meet. But I can say they had two video cameras and each presenter had a wireless lavalier mic. But I have no idea how they turned out and I don’t know when/if they plan to release anything. Regardless, I’ll post a note when/if they go up.

They’re being processed as we type! They should be done soon, but it does take a little time to combine two cameras, sound, and slides. 🙂

Fantastic news David, many thanks for checking in on that. If you want copies of the slides I used in this piece, they will probably serve as better source material than the pdf file used in the actual presentation. Just let me know.

Drew,

Bravo! I hope to forward this to some of my Union and Orchestra friends!

I remember taking a negotiations class several years ago, and one of the key points was to move beyond a winner-take-all mentality to a recognition that the final agreement will require compromise on both sides. In the mock negotiations we conducted, the most aggressive negotiators sometimes got better deals but in many cases never reached a deal at all. On the other hand, those who tried to understand the other side’s perspective and be transparent reached an agreement more consistently and left the bargaining table still able to talk with other side.

That’s certainly the idea but it all boils down to the people involved. The more outside agendas at play on both sides of the table along with the lack of transparent objectives, the more likely you can expect a less than ideal resolution.

Hokey smokes! Coming across this diamond of a blog post while MN Orch is imploding. Since it appears that this beloved ensemble is beyond salvation perhaps this can be a cautionary tale or list of suggestions for those who will endeavor to create something new out of the ashes.

Many thanks for the kind words Lizzie and I’m very glad to see you found the info useful.