The inaugural article for our ongoing examination of the Minnesota Orchestra Redline Agreement (MORA) will focus on proposed changes to the “home service area” definition and related contractual provisions for runouts. Given the increased attention throughout the field for augmenting outreach activity, i.e. events outside of the primary venue, it should come as no surprise that this agreement proposes numerous changes to how the organization implements those endeavors.

The Goal

What I hope to accomplish with this series is to provide a broader and more thorough understanding of the dynamic issues that go into a labor dispute. In the end, it’s much more than just compensation, benefits, musician compliment, and season length.

We’ll try to understand why clauses exist in the first place and what each side perceives as beneficial or injurious by modifying, eliminating, or leaving it untouched. Likewise, we’ll step outside of the world of sound bites, spin, and emotionally charged rhetoric by embracing a practical, evenhanded examination of the specific contractual language at core of this dispute.

[social-download button_id=”6fa40a3de4cf44280″ dl_id=”https://adaptistration.com/wp-content/uploads/MO-Redline-Agreement.pdf” theme=”blue” message=”Get social to download a complete copy of the MO redline agreement.” facebook=”true” likeurl=”CURRENT” google=”false” tweet=”true” tweettext=”I just downloaded the @mn_orchestra redline agreement at @adaptistration!” tweeturl=”CURRENT” follow=”true” linkedin=”true” linkedinurl=”CURRENT”/]

Ground Rules

- Avoid universal application. Perhaps one of the most important bear traps to avoid throughout this process is to assume that these issues are universally applicable to all orchestras; simply put, they aren’t. Just because the Minnesota Orchestra does something, doesn’t mean the same should hold true somewhere such Omaha and vice versa.

-

Understand the acronyms.

- MOA = Minnesota Orchestra Association (the board and/or executive management)

- MMO = Musicians of the Minnesota Orchestra

- MORA = Minnesota Orchestra Redline Agreement (the version submitted to musicians as their last official offer and subsequently voted down on 9/29/12)

- CBA = Collective Bargaining Agreement (also known as “the contract,” “master agreement,” or simply “agreement”).

- First hand clarification. When possible, additional insight, justification, and rationale behind why changes have been presented and/or why changes are opposed will be provided by official MOA and MMO spokespersons. If such information is provided after an article is published, it will be included as an article update.

- Irreproachable comments. Comments are always welcome but readers are encouraged resist the temptation to submit a comment when upset. If you aren’t already familiar with Adaptistration’s comment policy, please take a moment to review (via the “Blog Policy” tab).

- Interconnectivity. Although we will be examining groups of related terms in each installment, it is important to remember that very few of these issues exist in an institutional vacuum; meaning, just because correlations aren’t made between one or more contractual items doesn’t mean they don’t exist. It is recommended that following each installment, readers think back to previous posts and attempt to identify any potential connections.

What Is a Redline Contract?

Simply put, a redline contract (sometimes called markup or strikeout) is a version of proposed modifications that show:

- The original language.

- Modifications in the form of strikeout and bold formatting; the former being a removal with the later an addition or modification.

Depending on where the revision process is, redline contracts come in varying degrees of detail but it is normal for final versions to include every possible change, right down to modified section and subsection numbering. The MOA redline agreement used for these purposes is an example of the latter.

Ignoring The Inconsequential Stuff

In order to establish clear parameters, let me be clear that we will be skipping over housekeeping markups, such as changes to article numbers, dates, and all of the bits and pieces that need to change.

Article II Definitions & Article XIV Runouts

Section 2.6 Home Service Area - click to view

Section 14.4, 14.5, 14.6 Runouts - click to view

Quantitative Summary

This language exists in order to delineate when the employer is obliged to follow typical on the job standards and conditions (i.e. work rules) at locations within a prescribed radius and when it must institute additional measures and/or adhere to modified work rules. The bulk of “home service” activity occurs in the primary concert venue; common types of services outside this distinct area include runouts and tours, which are defined respectively in Section 2.12 and Section 2.15.

However, increased interest in outreach activity is spurring changes to traditional home service area definitions. Typically, employers have been seeking broader definitions while musicians express concern over dynamic consequences and diminished return on investment.

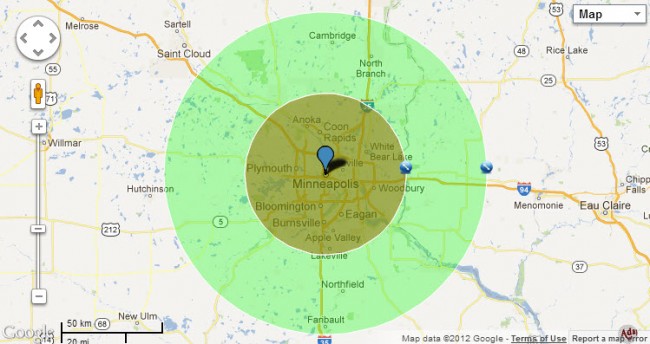

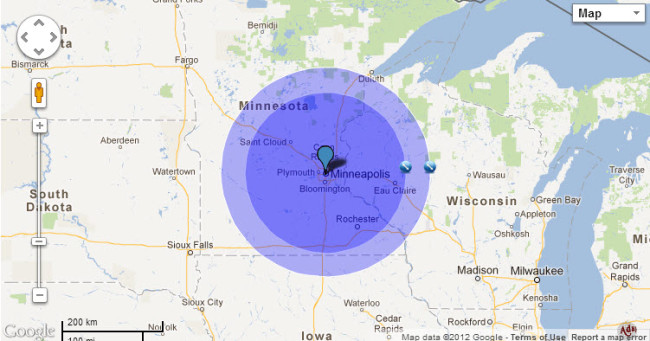

In this instance, the MOA is seeking to double the home service area radius in addition to expanding the maximum distance for runouts to include a host of cities as far away as Northern Iowa and the south-western tip of Lake Superior.

Services beyond the proposed 130 mile radius will be defined as tours and are therefore subject to conditions under those provisions. We’ll be examining those proposed changes in a subsequent article.

Management Perspective

Doubling the home service radius from 25 to 50 miles would clearly provide reduced operational expenses for increased activity outside of the home venue. For services outside the home radius the employer is obliged to provide bus transportation, meals, and day rooms during instances with large gaps between services along with providing minimum periods of rest before the end of the final runout service and the next scheduled service.

[quote float=”right”]The larger home service area affords the MOA with opportunities to increase artistic activity…without incurring much, if any, additional costs.[/quote] The larger home service area affords the MOA with opportunities to increase artistic activity in the greater Minneapolis metropolitan area, yet outside of the primary concert venue, without incurring much, if any, additional costs.

The increased runout radius seems to target a few key communities including, but not limited to, Mason City, IA to the south; La Crosse, WI to the east; and Duluth-Superior, MN to the north. The potential here is in the form of tapping into communities that have smaller budget professional orchestras and therefore, an established interest in live classical music concert activity.

Eliminating travel pay and limits on numbers of runout events (Section 14.4 and 14.5), doing away with securing committee approval before runouts over 100 miles can be scheduled (section 14.4), and removing required days off following extended distance runouts and two-for-one service credits against maximum numbers of services per week (Section 14.4 and 14.5) allow the employer to schedule related concert activity without restrictions and at lower direct and indirect costs.

Musician Perspective

[quote float=”right”]From an employee’s perspective, reduced cost doesn’t necessarily mean reduced price. [/quote] From an employee’s perspective, reduced cost doesn’t necessarily mean reduced price. In this instance, the price is perhaps best defined as a combination of monetary compensation, artistic contentment, and long term stability. In short, having a job that is not only worth obtaining, but keeping.

Establishing a home service radius that maximizes artistic quality and workplace satisfaction is determined by a sustainable balance involving travel time, quality of performance environment, and recuperation between services. An acceptable home service area is a key component in maximizing artistic quality and defining a satisfactory radius is typically the byproduct of trial and error over several decades.

The proposed changes to runout work rules potentially shift the overall price from one stakeholder to the other. For musicians, the costs can be literal as in the elimination of travel pay but the lion’s share are absorbed in increased fatigue and decreased time for personal practice and development.

Observations

Employer and employee positions here are comparatively self evident; the MOA does not believe it is unreasonable to expect musicians should travel longer distances for home area activity at their own expense as well as runout services with fewer restrictions and without consideration to time between multiple services. Conversely, the MMO likely believe the existing terms promote a sustainable balance that optimizes artistic quality and workplace satisfaction.

Employer and employee positions here are comparatively self evident; the MOA does not believe it is unreasonable to expect musicians should travel longer distances for home area activity at their own expense as well as runout services with fewer restrictions and without consideration to time between multiple services. Conversely, the MMO likely believe the existing terms promote a sustainable balance that optimizes artistic quality and workplace satisfaction.

Now, before jumping to conclusions or searching for some sort of compromise position, it would be useful if data existed to help determine a prescribed course of action.

To that end, the MOA would need to conduct market research into expanding service activity vis-a-vis the extended 50 mile home service area radius as well as the increased maximum runout distance. In order to determine the overall impact on annual income/expense, it is a comparatively simple matter to then juxtapose costs associated with those events under the existing and proposed contract terms.

This sort of research typically includes determining not only market potential but whether or not that activity might inadvertently produce a detrimental impact on ticket sales at the primary venue and whether increased marketing expenses related with developing a remote audience base produces a worthwhile return on investment while avoiding a long term drop in marketing performance (i.e. how much it costs to sell a ticket).

Directly related to the quantitative analysis are the host of dynamic concerns associated with the artistic product; which is simply antiseptic phrasing for how much negative impact this has on musicians and overall music making. This is the heart of where most conflict occurs whenever orchestra associations and musicians disagree about the impact work rules changes have on artistic excellence.

For example, as an orchestra grows and begins to pay a living wage musicians anticipate traveling less, as compared to a “Freeway Philharmonic” based livelihood, and reduced commuting will facilitate increased personal practice time and reduce fatigue. When optimized, the employer benefits from a higher artist return on investment for musician expenses.

Finding the right balance is an ongoing process and moving too far in any direction or introducing substantial deviations can produce unanticipated consequences.

In Closing

During the bargaining process, both parties should be able to provide quantifiable evidence to support modifying or maintaining current terms. In order to reach an informed agreement, useful tools in this process include the aforementioned market research reports, fatigue related grievance records plus productivity reports (sick days, etc.), critical reviews, music director assessments, regular workplace satisfaction studies, etc.

In addition to this material, both sides will apply varying degrees of notional perspective in order to convince the other of an optimum course of action. Moreover, placing relative value on groups of terms within the larger bargaining environment and a willingness to identify final terms that support a mutually agreeable unified institutional vision is a healthy approach to avoiding, or ending, conflict.

Ultimately, this initial peek inside the much larger proposal will prove to be a useful foray into helping develop a practical outlook on the dispute.

I do not see anything related to mileage reimbursement for home service area activities. The challenge and issues with the difference between a 25 and 50 mile home service area radius really tie into if there are service conversions (as is being pushed by many orchestra managements in new contracts) and how many are allowed in a given week. If there is a 9-service week and there is a requirement for that many service conversions, then there could theoretically be well over 900 miles (worst case) of driving within a given week for service conversions without any mileage reimbursement. This could be three gas-tanks full of gas and $150 to $175 of out of pocket expenses to the musician. It could be much more expensive if the musician has a large instrument (and thus a large car and lower gas mpg) and has to take it on a series of service conversion jobs. A string of service conversions like this could result in a big costs to the musician.

For the sake of readers who may not be aware, would you mind defining “service conversion” within the context of your comment?

Drew;

As I am sure you know, most professional full-time orchestras have a number of services per week, either orchestra rehearsal or performance services. The orchestra that is local to my area typically has 8 services per week, and sometimes 9 services per week, depending upon the contract.

Service conversion is when the orchestra management requests orchestra members to work in another capacity rather than in the context of an orchestra rehearsal or a performance. To understand the basis for this, go to the following link and at 5:00 to hear Leonard Slatkin discuss the change from limiting financial losses to turning the orchestra into a money making venture.

http://minnesota.publicradio.org/www_publicradio/tools/media_player/popup.php?name=minnesota/podcasts/mpr_news_update/2012/10/news_update_20121010_64

So service conversions can have the orchestra member going out at the requirement of the orchestra management and doing performance based services as soloist, small ensemble member, or in a non-performance role, such as teaching, educational talks, or in some extreme cases working in the orchestra administration offices, or even helping fix or repair the orchestra hall facilities (as was proposed by the CEO of the orchestra in my community). The goal of service conversion is to utilize the musician in an auxiliary role were the musician is not paid for the non-orchestra rehearsal or performance role, since they are already technically on the pay-role and are being paid by the organization.

The point of all of this is that the orchestra managements are seeking to become musician providers for private parties, weddings, church services, and other events that require music, or teaching and educational activities. The orchestra would charge the people wanting orchestral musicians there, but the musician will not get extra funds for these events…again, since they are already technically on the pay-role and are being paid by the organization. Some orchestra managements are willing to toss some extra cash the musician’s way, but usually not much. With service conversions the orchestra management essentially becomes a music management/contractor organization to many outside musical events…not just orchestra concerts.

Many new contracts coming from management these days have some type of service conversion being requested. For my comments above, if the home service area is expanded, then these other events can become part of these service conversions.

I like your analysis. I would add that “personal practice and development” is for the benefit of the orchestra, as staying on top of one’s game is necessary to create a great orchestra sound. In addition, playing concerts in less-than-ideal venues has at least two negative effects; it takes the orchestra a step backwards in developing/maintaining a great sound, and it presents the orchestra to the public in a venue in which it is impossible for it to sound really great, thereby possibly lowering the public perception of the value of the institution.

That’s a good observation Susan; as it is, most CBAs include language along the lines that each musician is responsible for maintaining his/her respective skill set. Consequently, an organization must juggle where it feels the musicians are at a point where they have adequate time for personal preparation. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this is where potential conflict arises during bargaining sessions.

Hi Drew,

I’d love to hear some more of your thoughts about this added focus from orchestra managements on run-outs and touring. I’ve held jobs with two different orchestras, 2007-08, the group I in which I played did a whole lot of touring, and sort of dangled a carrot of promised wage increases if we became a more state-wide orchestra. In the first two years of my current employment (started in late 2008) my orchestra did very little touring. Then last year a great number of run-outs and tours were added, and even more are planned for this year. I can’t really see that these additions have been all that successful, attendance at such concerts has been mostly pretty low, it doesn’t look to me like they are well marketed. Surely there must be added costs to the group as a whole to provide buses, transport large instruments, chairs, stands, etc. not to mention things like per diem for musicians and staff, do you think it really makes financial sense for orchestras to go in this direction? It seems the MOA thinks that it does, or they wouldn’t be going after these provisions of the contract, but that also begs the question, if they think this will allow them to increase revenue, why are they trying to cut wages so much at the same time?

Thanks for your comment Andrew and those are some intriguing observations, perhaps the most relevant in this instance is the actual cost of launching concert activity in a remote market (i.e. runouts). In short, it is akin to any business moving into a new market; there will be increased startup costs and after a prescribed period of time, the new activity will begin providing the desired return on investment.

In the case of an orchestra, that return (in the short to mid range) could include increased contributed revenue from foundation or large donor sources as well as an influx of annual giving from smaller donors.

The risk here is launching these activities. A cash strapped organization will have a much more difficult time since those startup costs (dollars and human resource time) will have to be reallocated from other efforts. Ideally, an orchestra will conduct a fair amount of initial research into the effort(s) (including scouting venues with the artistic admin, ops manager, MD, and musician reps) and secure funding to offset the initial costs.

In lieu of securing additional revenue, the organization can go the reallocation route and that certainly can include shifting financial resources from something like musician compensation to cover start up costs. Granted, that’s a very academic outlook and any organization considering such an approach would be wise to consider the dynamic range of potential responses.

This is very insightful analysis, especially for someone (me!) who’s never seen contract language before. Thanks so much for taking the time to put it up. I’m curious as to the difference in language between the highly specific (ex. Section 14.3) and the general (ex. new section 14.7). Why are some clauses left up to discretion and some so regulated? Are the specifics maybe a necessary, but sad side effect of a large organization with many stakeholders and perhaps a degree of mistrust and/or disagreement between the sides?

Instead of highly regulated travel wouldn’t it be better if the ED would be able to say “Hey we’ve got this great opportunity in Mason City to expand the orchestra’s reach, and we know that means a bit more travel for you but we promise to respect your time and not over schedule you or stray from our core goal of great music in our home city…”

And then maybe the musicians would come back and say “that gig sucked, lets not do it again” or “that was really rewarding and worth the travel”

And then the ED could say “Ok, sounds good, thanks for giving it a shot, we won’t do it again” or “we made a bazillion dollars and sold a hundred more subscriptions so even though it sucked it was worth it…”

(pardon for the ramble)

Thanks for the questions Zach, I’ll do my best to provide some insight but it should be noted that I don’t know for certain the history or justification for the language in the MO contract; as such, I’m speaking more from a general point of view.

Q: Why are some clauses left up to discretion and some so regulated?

A: This is an excellent example behind something that is a reaction to a previous issue. Language such as “best efforts” implies a sort of working understanding and trust building but if the respective party fails to abide, the other has recourse for filing a grievance (which typically requires citing specific contract language). Whereas specific language is the byproduct of either one side being very firm on a position or both sides mutually agreeing that it is easier to have detailed language (i.e. the ops department knows exactly how to operate instead of having to guess).

Q: Instead of highly regulated travel wouldn’t it be better if the ED would be able to say…

A: Sometimes yes, sometimes no. In the example you provided, assume that there is no language preventing the association from scheduling such event. Also consider that execs come and go so one may have a good relationship with musicians and diligently ask and abide (more often than not) with musician feedback. But another exec may do whatever s/he feels is in the best interest regardless of musician input. At the same time, it’s worth pointing out that a common middle ground (contractually speaking) is to include a set number of variances the association can implement in a given season and the employer can always request a variance.

Your subsequent example where musicians may think “that gig sucked, let’s not do it again” is exactly the sort of occurrence that leads to contractual language, especially if they express those sentiments to management and they fall on deaf ears.

In the end, the sort of respectful, mindful labor relationship you described is exactly the sort of environment that should exist; the trouble is what does either side do if it doesn’t? What does an exec do if the committee is a bunch of bitter, angry musicians out for payback against transgressions from a predecessor and what do musicians do when trust is returned with abuse? The result is contract language.

Thanks for the thorough and quick reply. It reaffirms for the me the sentiment of “sad but necessary” (and I hadn’t considered the effect of management changes so thanks for pointing out that aspect). A quick follow-up- in your knowledge/experience do organizations with a history of good labor relations tend to have more variances in their contract language?

Neither since most sides tend to favor a safe-than-sorry approach. The historical record worth observing is what’s called “past practice” and in this application, it would apply to formal variance requests and subsequent response.

I can offer an example of contract language arising from a similar discussion. My orchestra’s CBA has an exception to the run-out language allowing services in a particular city to be home services even though the city is a few miles outside the home service area.

Originally, management wanted to expand the home service area and musicians did not want to. We had played one or two concerts in this particular city, and management thought we might be able to develop a longer-term relationship with the presenter if we could keep costs down. Musicians thought that would be a benefit worth the cost to us, and agreed to allow that city to be in the home area. As it turned out, we were able to play more concerts in that venue, at least for a few years.

This is an example of how having a plan and doing some research about not only the pros and cons of a proposal but also its feasibility can help smooth the process of compromise.

thank you for your calm and informative description of the contractual process. I’ve been interested in the MOA/MMO negotiations, as I live in Minneapolis and occasionally attend orchestra functions.

There are many items which might (not) appear in media coverage of this, and which are overlooked because the two sides of the negotiations both consider it so obvious as to be moot – but the side-line music-loving non-musician audience doesn’t. You addressed travel costs.

Many can personally relate to the problems of job-related travel, meal reimbursement, milage costs, etc. They also have a general idea of how much this would represent in actual dollars.

Last week @ the MMO concern, a friend expressed mild surprise that the musicians are responsible for the purchase, maintenance, & repair of their instruments. It is obvious, given any amount of thought … but it is a financial consideration which might not appear to non-musicians.

He was equally surprised when I offered him an idea of how much some of the instruments might cost. A quick google this evening indicated that you could easily purchase professional quality instruments running around

flute $10,000.

oboe $9,000.

clarinet $5,000

English Horn $9,000

Bassoon $25,000.

Most ordinary people who played in a high school band would think of the cheap student model flute I own, which would might cost me around $200 today. Not the hand-made ones that cost as much as a great down-payment for a house.

That’s absolutely correct in that the vast majority of musicians are required to provide their own instruments. There are some exceptions, especially larger budget orchestras that own instruments as investments or because of their unique nature.Similarly, most of the percussion instruments are provided (although many percussionists still purchase their own, especially in orchestras that don’t or can’t provide practice space).

String players tend to absorb the brunt of instrument costs where a good quality instrument is anywhere from $30,000-$250,000. Add to that bows and maintenance (which can easily reach $100,000 over a career lifetime) and it’s an extraordinary cost to carry.

It’s also fair to point out that some orchestras provide special loan programs and in a few cases, outright supplemental funding, but that’s usually limited to the larger budget organizations.

Drew, I think it’s important to linger for a moment on your “freeway philharmonic” point. One of the big drawbacks of the freeway philharmonic job is the stress of driving to different locations on one’s own, often in rush-hour traffic.

A job where the orchestra plays mostly in one regular venue and provides a bus for run-outs could reduce that stress considerably. When the orchestra provides a bus, musicians are responsible to get to the bus on time, usually in a central, familiar location (concert hall, symphony office). After that, it’s the orchestra’s responsibility to get the musicians to the concert on time. If there’s a huge traffic jam or a snow storm, the whole group is late together. When the musicians are responsible for their own transportation to more distant venues, the stress level and possibility of mishap increase.

If an organization is planning to add a significant number of these services, then it is adding a significant burden for its employees (in addition to the cost another reader mentioned above).

I know this post has been around a long time, but recently it occurred to me that there’s a clear and practical reason for section 14.4, and that’s inclement weather. It just so happens that my orchestra has a run-out concert tonight two and a half hours away and there’s a winter storm sitting over our city dumping snow on us. I’ve never lived in Minnesota, but I’ve lived in Ohio, and we used to have bad winter storms in late April and even early May. The weather obviously creates a safety issue for traveling musicians, and I’m sure the organization takes a hit if conditions are so bad that travel becomes impossible and a run-out concert has to be cancelled.