Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) principal flute Elizabeth Rowe is suing her employer “to recover over $200,000 in unpaid wages unequal to the pay of a comparable male musician.” We’re going to examine the bulk of her complaint on a point by point basis.

It would be surprising to see the suit go to trial but if it does, it would undoubtedly have profound impact on how orchestras approach individual musician agreements.

If Rowe’s lawsuit succeeds, it could serve as the starting point for similar suits from women principals who may begin to question if they are the victim of bias, either unintentional or not.

Disclaimer

It’s important to keep in mind that legal complaints are accusations and all defendants are presumed innocent until and unless proven guilty.

This review is provided for general informational purposes only and is not to be relied upon as legal advice. The author does not make any representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability with respect to the complaint.

We’ll be examining some, but not all, of the complaint’s allegations. Focus will be directed toward items that in my professional opinion are paramount to the case and are best served for review in this format.

Allegations

- At all times relevant, Defendant BSO was required to pay comparable pay to plaintiff for work comparable to that of a male for work of substantially similar skill, effort and responsibility under similar working conditions, and was required not to discriminate on the basis of gender in any way in the payment of wages.

This is one item both parties in the suit appear to agree on. According to a statement from the BSO to KPCC 89.3, the organization is devoted to equal pay for equal work:

The BSO is committed to a strong policy of equal employment opportunity and to the practice of comparable pay for comparable work, as well as abiding by the Massachusetts Equal Pay Act.”

- As late as 1970, the top five orchestras in the U.S. had fewer than 5% women. It wasn’t until 1980 that any of these top orchestras had 10% female musicians. Because of the history of excluding women from orchestral positions and orchestral leadership positions, any qualification or criteria favoring a prior history with other preeminent orchestras was a tainted practice which had a known gender bias favoring males and would have a discriminatory effect on women.

Assuming those details are accurate, it would be fascinating to see how those ratios developed over the subsequent decades. At the very least, the number of orchestras included in the sample from 2000 forward should include the Big Eight. It would also be worthwhile to extend the research out through all 52-week orchestras.

While things have certainly improved since those remarkably low ratios from the 70s and 80s, it’s good to have them included in the lawsuit to remind everyone just how much sex-based hiring bias has shaped the field of professional classical music.

- From 1995 to the present Dr. Mahzarin Banaji, a professor at Harvard University, published research and tools to measure and identify implicit bias. In 2017, Dr. Banaji specifically referred to the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s blind auditions as one way of reducing implicit bias against women musicians in discussing a forthcoming National Geographic segment on reducing gender bias in pay and in selection.

- Blind orchestra auditions significantly reduce sex-biased hiring and increase the number of female musicians, reducing the gender gap in symphony orchestra compositions. The BSO was aware in 1952 that using a screen to conceal candidates from the jury during preliminary auditions increased the likelihood that a female musician would advance to the next round.

- However, even blind auditions still skewed male. The research then revealed that the sound of female musician’s heels revealed the gender of the candidate. When the shoes were removed 50% of the candidates reaching the final round were women. Research demonstrated that during the final round, “blind” auditions in major orchestras in the US increased the likelihood of female musicians being selected by 30%.

- The blind audition process increased overall orchestral standards while bringing more non-white, non-male applicants away from the sidelines to principal positions from which they were traditionally excluded. Before the blind audition, the music director or orchestral committee could pick the players he or they knew and wanted. As a result of the blind auditions, the best musician, regardless of gender, was selected. Also, as more and more musicians are trained at the highest levels possible, the competition is fierce.

This quartet of allegations is particularly fierce. It goes a long way toward reminding all parties involved that even with the best intentions, inadvertent bias is a tangible, and quantifiable, hazard.

When juxtaposed with the BSO’s historical leadership implementing the blind audition protocol, it demonstrates that process alone is no guarantee of a bias free audition environment.

- When Ms. Rowe was hired in 2004, the principal oboist (John Ferrillo) was performing work that is substantially similar, in that it requires substantially similar skill, effort and responsibility and is performed under similar working conditions. Both the principal oboe and principal flute are leaders of their woodwind sections, they are seated adjacent to each other, they each play with the Boston Symphony Chamber Players, and are both leaders of the orchestra in similarly demanding artistic roles.

Undoubtedly, this would become one of the most contentious artistic based arguments if the suit went to trial. Ferrillo has already gone on record stating “I consider Elizabeth to be my peer and equal, at least as worthy of the compensation that I receive as I am.”

But the question about whether the positions share equal duties and responsibilities is one where the employer could push back. What’s been fascinating so far is the lack of input from or questions directed toward BSO music director, Andris Nelsons. He will be the key BSO executive entrusted with the authority for setting the standards on whether the duties and responsibilities between principal oboe and principal flute are substantially similar.

When working on individual agreements, I routinely recommend to clients that if they are unable to come to an agreement on the importance of (and therefore value) any artistic based issues, insist on having the music director weigh-in on the topic. In most cases, the musician’s position will be validated by the music director.

Allowing the music director to provide guidance also provides a convenient way for the administrator conducting the negotiations on behalf of the employer a way to save face while consenting on the point.

It’s worth pointing out this is where the bulk of disagreements emerge within social media-based discussions I’ve observed.

Orchestra stakeholders gravitate toward traditional artistic subjects like a moth to flame. While they are certainly worthwhile discussion topics, they do tend to suffer from a glut of opinion influenced by the same sort of unconscious bias referenced in the complaint.

- The collaboration between the principal oboist and the principal flutist is a pivotal relationship and a cornerstone of the orchestra. Of all the principal chairs, the flutist and oboist are the most comparable based on number and type of contributions in the pieces played, the prominence of their contributions, and the similar needs of their respective wind sections.

This is one of the strongest artistic based assertions throughout the entire complaint. Even if the other party attempts to focus on presenting the positions as a hierarchical relationship, it’s next to impossible to argue their combined impact.

- The principal flutist and oboist are often among the top five highest paid members of peer orchestras in the U.S.

It certainly is. This is easily quantifiable by using nothing more than using orchestra tax returns. My direct experience with orchestras where musicians aren’t always in the top five paid employees confirms this as well.

- Upon information and belief, the BSO had a policy of considering prior salary earned by an applicant.

This is an excellent example of an assertion that is almost certainly backed up by verifiable evidence. It’s also why I recommend clients maintain fastidious notes when bargaining for their individual agreements. All face to face and telephone-based conversations should include notes that are sent to the employer representative in order to develop a common understanding and correct any miscommunication (even if both sides ultimately disagree on interpretation).

- Male principal players playing instruments traditionally played by men were often paid more than female principal players playing instruments traditionally played by women.

- The BSO’s Principal Oboe, Principal Viola, Principal Trumpet, Timpani and Horn are all positions which have historically been held by men and are currently all held by men. On information and belief all five positions are paid at a higher rate than that paid to Ms. Rowe based upon gender and past salary history.

- The following principal chair positions at the BSO, in which males play instruments traditionally played by men, were paid significantly more than Ms. Rowe, who was performing comparable work with at least comparable skill, effort and responsibility, in a similar location:

the Principal Oboe was paid 200% of base

the Principal Viola was paid 175% of base

the Principal Trumpet was paid 173% of base

the Principal Timpani was paid an estimated 165% of base

the Principal Horn was paid 162% of base

while Ms. Rowe, the Principal Flute, was paid 154% of base pay.

This is where the complaint become less cut and dry. In order to conduct this sort of apples-to-apples comparison, you need to examine the specific language of each individual contract in order to determine if the values used in these percentages includes compensation for issues unique to that instrument.

For example, among the instruments included in this list, it is not uncommon for oboists and timpanists to ask for financial terms to offset their cost of ownership expenses, which run higher than their peers. Some employers agree, others don’t. For those who do, how they structure that payment could have an enormous impact on this sort of lawsuit.

Simply put, the devil is most certainly in the details.

Example:

- Oboist successfully negotiates a $2000 annual financial benefit that both parties agree offset the cost of making reeds (equipment and time).

- Employer insists on including that figure in the musician’s wages and distributes it into equal installments coinciding with the existing payroll schedule.

In this example, the reed expense benefit would be included in the 200% of base figure. The problem is financial benefits to offset reed expenses isn’t something applicable to flutists.

While this doesn’t preclude the basis of the lawsuit, it does muddy the waters when it comes to determining whether the BSO is favoring male principal musicians.

All of this is an excellent example behind why I recommend the employer separate non-artistic financial benefits into mutually exclusive line item disbursements.

If the goal is to conduct a fair and comprehensive analysis, the full scope of each principal musician’s individual agreement will need to be evaluated. This includes not only the final written terms, but all written communication related to negotiating along with statements from related parties to verify if the final financial terms include any non-performance related expenses.

- The BSO flute section currently consists of three women and one man. The BSO oboe section is all male. The BSO’s one harpist is female, as was her predecessor.

This is a particularly interesting item and I’m surprised it didn’t include an analysis of financial terms among the non-principal male and female individual agreements. So long as the positions have equal titles with related duties and responsibilities, it would be fascinating to see if any alleged disparities extend into fixed chair wind positions.

- Ms. Rowe and Mr. Ferrillo, principal wind players in endowed chairs at the BSO, are among the top performers in the world in their respective instruments and have substantially similar skill, effort and responsibility in their positions except that Ms. Rowe performs more frequently as a soloist.

Ms. Rowe’s frequent work as soloist is something her suit mentions via multiple items. It certainly goes a long way toward verifying her assertion that the organization places great value on her artistic prowess.

At the same time, this is another excellent example of a financial term that potentially muddies the waters when comparing salary figures.

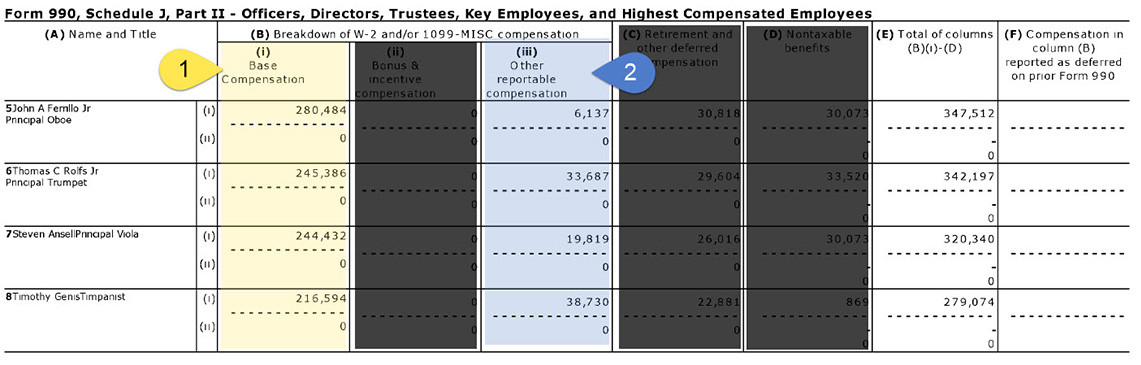

When compared to the reed expense example, solo compensation is far more likely to be paid outside of wage-based compensation. However, what’s not clear in the suit is whether the percentages used for determining alleged discrimination include the “Base Compensation” figure alone as included in the BSO’s Form 990, Schedule J, Part II B.i. or if it includes that and B.iii (Bonus & Incentive compensation).

Here are those figures from the BSO’s 2015/16 990 showing only the musicians included in the complaint’s comparison. You can see just how much the compensation from column iii (in blue) varies:

This all circles back to the critical step of evaluating not only the dollar amounts for wages, but the related financial terms and disbursement structure, all of which impact determining potential pay discrepancies.

- The BSO discriminated in compensation by providing additional assistance to reduce the physical demands required of the principal oboist. The BSO, in addition to the overscale pay, provides and pays for the use of an assistant oboist for approximately 6-12 weeks per season to assist the male principal oboist, an added benefit of approximately $18,000-$35,000, while the female principal flutist is provided no assistant.

This is going to be a very tricky allegation to pursue. There’s no denying that not having an assistant principal position places a tremendous amount of additional work load responsibilities on the principal musician.

The problem is these positions aren’t something directly within the employers control. Instead, they must be defined via the collective bargaining agreement. It’s a scenario I’ve run into with clients on several occasions in the past decade alone and in some cases, the principal position without the assistant can leverage that into additional overscale wages, additional time off, or a combination of both.

If Rowe was asking for those benefits but routinely denied, it will be an uphill battle for the employer to defend.

But let’s say the employer is in favor of adding an assistant principal flute position and proposes it during CBA negotiations but the musician’s bargaining committee shoots it down. What then?

But let’s reverse that scenario and say the orchestra committee has been pushing for the assistant flute position but the employer refuses to acquiesce. Moreover, they refuse to provide any additional benefits to Rowe’s individual agreement in order to help offset the disparity with peer principals. That certainly wouldn’t look good.

Granted, those are strictly academic exercises, but they’re provided here to demonstrate how the lawsuit can easily reach past the scope of individual agreements.

- The BSO also discriminated against Ms. Rowe by the nature of her personal contract, as it provides certain males performing comparable work a fixed percentage contract ensuring these males get automatic increases whenever the base rate is increased. No female is on an automatic increase contract with respect to the orchestral base rate.

- The BSO discriminated against Ms. Rowe by paying her an above scale dollar amount which she is required to renegotiate to get pay increases, while certain males enjoy being on automatic pay increases.

If accurate, this is going to be one of the most damaging allegations.

When advising clients on individual agreements, one critical term to include is language stating the overscale amount should be a percent over base pay and not a fixed dollar amount. If the employer insists on a fixed dollar amount, the musician should insist on annual increases equal to the amount of average base musician salary increases over the past decade then set the agreement’s end date as far into the future as possible.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, most employers push back hard on this item and insist on the fixed dollar sans increases because it forces the musician to approach the employer each subsequent season to fight for the cost of living increase (which is Ms. Rowe’s point via item 54).

The only plausible defense justifying this disparity would be a change in executive leadership that occurred at the time Ms. Rowe began negotiating terms for her individual agreement.

I’ve seen this happen at some orchestras. In those instances, an incoming CEO will adopt the “there’s a new sheriff in town” attitude that no percentage based overscale will be allowed. The initial musicians to bear the brunt are incoming principals, but the CEO may not be able to amend existing agreements if the language is structured in a way that prevented the employer from unilaterally re-opening an agreement without consent from the other party.

Given the long tenure of the BSO’s Managing Director (they don’t use the title CEO) that predates Ms. Rowe’s first year with the orchestra, it’s unlikely that scenario is applicable in this instance.

- Annually, each August, Ms. Rowe has requested to renegotiate her contract to increase her overscale pay for the upcoming year, and in each year asked to be paid equal to that of Mr. Ferrillo. In every year including 2015, 2016 and 2017 the BSO set her overscale rate based on an evaluation of her demand, and in each year the amount was significantly less than Mr. Ferrillo, demonstrated by a memorandum describing her overscale salary which was then applied in every paycheck for that year.

This item is an excellent example why orchestras desperately need to adopt individual agreement compensation policies for musicians. It would be useful to examine the communication related to each year Ms. Rowe approached the employer for new terms.

Per my point above about the importance of maintaining copies of all communication, these would undoubtedly become crucial documents in any sort of discovery phase.

Retaliation

The complaint continues by listing allegations categorized as retaliation for Rowe’s assertions that the employer was engaging in gender bias pay discrepancy.

- The BSO knows retaliation is prohibited for Ms. Rowe having opposed gender inequity in salary, and/or remuneration of all types and working conditions.

- In December, 2017 the BSO asked Ms. Rowe to be interviewed for a National Geographic documentary hosted by Katie Couric, renowned television reporter and host, as the face of the BSO in an episode segment about the practice of blind auditions that the BSO put in place in 1952. The segment, focusing on gender, the key social issue of the time, was to include the recreation of an audition with a female BSO musician playing on one side of the curtain and a few members of the committees who typically judge the auditions on the other side.

- The BSO and National Geographic planned to shoot this segment at Symphony Hall on Friday January 5, 2018.

- Taryn Lott, Assistant Director of Public Relations for the BSO, at the request of Lynn Larsen, asked Ms. Rowe to participate, and noted the episode would ask her to play something that she played in her audition, and to speak about her personal experience with auditioning and what it is like to play with the orchestra. The additional stories in the episode would include interviews with film star and gender equity activist Geena Davis about the Institute on Gender in Media, and with Harvard Professor Mahzarin Banaji about implicit bias for gender, including how the BSO’s blind auditions were designed to address implicit bias.

- Ms. Rowe replied that she was willing to do so and mentioned her concerns about conduct and treatment on the basis of gender within the BSO, including known salary discrimination. The BSO immediately rescinded her invitation to appear on this national television program on gender equity.

- By her conduct Ms. Rowe (i) opposed an act or practice made unlawful by this section; (ii) made or indicated an intent to make a complaint about unequal pay, (iii) and was about to testify, assist or participate in any manner in an investigation of unequal treatment of women on the basis of gender including pay, in a national discussion by an investigative journalist and prominent academic and entertainment experts in the field; and (iv) disclosed again to the employer her wages and inquired again about or discussed the wages of John Ferrillo and other holders of principal chairs at the BSO.

- The BSO denied Ms. Rowe the opportunity to participate as a witness in a national matter of great social concern in January 2018, and denied her the opportunity to use her acknowledged preeminent talent and recognition to further oppose unequal compensation for similarly situated women.

- The BSO damaged Ms. Rowe by this retaliation because of her protected conduct.

- The BSO is aware of its duty not to retaliate against Ms. Rowe, in selection as the face of the BSO, as a soloist for the BSO or in donor retention or cultivation events, because of her opposition to unequal pay and treatment at the BSO.

This section is one of the more intriguing aspects of the complaint. If the allegations are accurate, it will be very difficult for the BSO to present a reasonable defense.

Next Steps

For now, everyone should be content with following developments as they unfold.

When it comes to musician individual agreements, the rabbit holes are numerous and deep. Resisting the urge to embrace snap judgements or assume all information is accurate and complete is strongly recommended.

At best, these issues should be the starting point in a much longer journey of discovery and education about the granular details distinguishing performance and non-performance related issues unique to each instrument.

In the end, it’s not just the terms, but how they are structured.

Much of these details are unknown and/or unconfirmed, so until that information comes to light, it’s better to operate in data-acquisition mode instead of tossing out bated questions and presenting assumptions as fact.